Believing in Unicorns

An Exultation of Mythical Beasts by Stephen D. Winick

Of all the creatures of myth and legend, from the scaly dragon to the cunning sphinx, the unicorn is the most beautiful and the most beloved. Although fierce and proud, he is noble and kind. While many magical creatures portend danger, the unicorn usually brings good luck. You can read of the unicorn’s exploits in ancient travelers’ tales, medieval bestiaries, and modern novels, or glimpse its image on monumental friezes, on intricately woven tapestries, and even—if you look very closely—in the stars.

For centuries, Europeans believed in the unicorn as a real animal that lived in a foreign country, such as India, Persia, or Abyssinia. It was not a magical beast, but a specimen of foreign zoology. This is not very surprising, for as Odell Shepard has pointed out, the unicorn is not as unbelievable as many real animals. “Compared to him,” Shepard opines, “the giraffe is highly improbable, the armadillo and the ant-eater are unbelievable, and the hippopotamus is a nightmare.” (Shepard p. 91) Still, the unicorn has always had mystical qualities, and gradually these overtook the animal’s purely zoological interest. Nowadays, almost everyone agrees that unicorns are magical, mythical beasts…even those who still believe in them!

An Indian Ass and a Healing Horn: The Ancient Unicorn

Belief in unicorns began in very ancient times; indeed, tracing it back, scholars find that the trail peters out as writings and artworks themselves become scarce. China and Japan have their own unicorn traditions concerning the ki-lin and kirin (you can see the latter pictured on the label for the beer of the same name), but the first European mention of the unicorn is by Ctesias, a Greek historian of the 5th century, B.C. Ctesias was a physician at the Persian imperial court, and wrote many books, none of which survives intact. In his book Indica, which describes India, Ctesias describes not only unicorns, but also griffins, manticores, and dog-faced men. Like many travel-writers of his time, Ctesias never went to India; instead, he claims to have based his book on the beliefs of Persians, and on first-hand accounts from travelers.

Indica survives in fragmentary summaries made by Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople (ca. 810-893 A.D.). In fragment 25, Photius writes:

As the first full description of a unicorn, Ctesias’s passage is of great importance to unicorn lore. Although the animal’s multi-colored appearance, jewel-like huckle-bone, and tri-colored horn do not survive to become part of most medieval or modern ideas of the unicorn, many of the other descriptors do: it is like a horse but not quite a horse, has solid hooves, is a fierce fighter and difficult to hunt, and has a long horn. Moreover, Ctesias describes in detail the healing properties of the unicorn’s horn, especially as an antidote to poison; this is a belief which survived for thousands of years. (The translation of this passage in Shepard [p. 28] states also that the powdered horn is a useful medicine.)

After Ctesias, Classical antiquity did not much love the unicorn, but our one-horned beast peeks around the edges of history. Aristotle mentions unicorns in passing, stating, “there are some [animals] that have but a single horn; the oryx, for instance, and the so-called Indian ass…. In such animals the horn is set in the centre of the head.” The Indian ass is the unicorn described by Ctesias, while the oryx is actually a two-horned antelope… but glimpsed from the side, an oryx can look like it has one horn. Caesar, in book 6 of his account of the Gallic wars, speaks of an ox shaped like a stag. “In the middle of its forehead,” he writes, “a single horn grows between its ears, taller and straighter than the animal horns with which we are familiar.” This is often taken to be a description of a unicorn, but Caesar goes on to describe finger-like branches on the end of the horn, leading others to interpret it as a reindeer, glimpsed from afar. Aelian, a third-century Roman historian, describes another unicorn, the “cartazon,” whose horn is black, and which “has a mane, tawny hair, feet like those of the elephant, and the tail of a goat.” Aelian describes it as a solitary animal with a very dissonant voice, and many modern historians believe he is describing a rhinoceros. Pliny the Elder further described unicorns, basing his knowledge mainly on Aelian. Among them, Ctesias, Aristotle, Aelian and Pliny state that the unicorn is similar to the ass, horse, antelope and goat, providing most of the ingredients for later conceptions of the animal.

After Ctesias, Classical antiquity did not much love the unicorn, but our one-horned beast peeks around the edges of history. Aristotle mentions unicorns in passing, stating, “there are some [animals] that have but a single horn; the oryx, for instance, and the so-called Indian ass…. In such animals the horn is set in the centre of the head.” The Indian ass is the unicorn described by Ctesias, while the oryx is actually a two-horned antelope… but glimpsed from the side, an oryx can look like it has one horn. Caesar, in book 6 of his account of the Gallic wars, speaks of an ox shaped like a stag. “In the middle of its forehead,” he writes, “a single horn grows between its ears, taller and straighter than the animal horns with which we are familiar.” This is often taken to be a description of a unicorn, but Caesar goes on to describe finger-like branches on the end of the horn, leading others to interpret it as a reindeer, glimpsed from afar. Aelian, a third-century Roman historian, describes another unicorn, the “cartazon,” whose horn is black, and which “has a mane, tawny hair, feet like those of the elephant, and the tail of a goat.” Aelian describes it as a solitary animal with a very dissonant voice, and many modern historians believe he is describing a rhinoceros. Pliny the Elder further described unicorns, basing his knowledge mainly on Aelian. Among them, Ctesias, Aristotle, Aelian and Pliny state that the unicorn is similar to the ass, horse, antelope and goat, providing most of the ingredients for later conceptions of the animal. Aristotle and Pliny, towering figures in European letters, were considered great authorities on many subjects for over a thousand years, so their writings carried unicorn lore well into the Middle Ages. But no text from antiquity could be more influential in keeping unicorn lore alive than the Bible, for the Latin and Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible familiar to all Christians in the Middle Ages mention the unicorn several times. This biblical unicorn seems to originate with a mistranslation. The Septuagint, those seventy-two Jewish scholars of Alexandria who first translated the Bible into Greek, between the third and second centuries, B.C., chose to translate the Hebrew word re’em as “monokeros,” literally “one-horn.” This became “unicornis” in both the Old Latin Bible and some passages of the vulgate Bible, and “unicorn” in the King James Bible. However, it is now fairly clear that the word re’em in fact referred to a wild ox or aurochs, and most modern English translations reflect this correction. Nevertheless, the older translations were literally taken as gospel throughout Christendom for over a thousand years, making belief in unicorns an article of faith to many believers.

A Virgin, a Lion and a Poisoned Pool: The Medieval and Renaissance Unicorn

As the world of antiquity gave way to the Middle Ages, the unicorn gained in fame and popularity. In fact, medieval and renaissance stories of the unicorn became so popular that in 1612 Petrus Plancius included a unicorn constellation, Monoceros, on his celestial globe, enshrining the magical beast in the stars.

As the world of antiquity gave way to the Middle Ages, the unicorn gained in fame and popularity. In fact, medieval and renaissance stories of the unicorn became so popular that in 1612 Petrus Plancius included a unicorn constellation, Monoceros, on his celestial globe, enshrining the magical beast in the stars.Throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, one belief about the unicorn from Ctesias’s earliest description remained the most important: its horn was a cure for all poisons and diseases. Variations on the tale also existed; in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Grail Romance, Parzival, the healing implement is a jewel found at the base of the unicorn’s horn. By the Renaissance, the story had grown so that the horn was said to sweat in the presence of poison, making it a poison-detector as well as an antidote. Wealthy people went to great lengths to procure what they believed to be the horns of unicorns, largely for their supposed medicinal value.

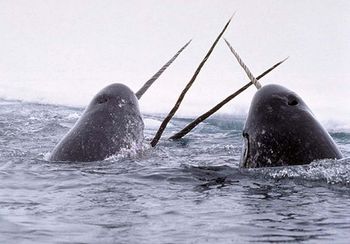

Most of the “unicorn’s horns” on the European market were actually the tusks of the narwhal, a whale that grows one long, twisted tooth resembling a horn. Through the demand for narwhal tusks, the unicorn belief affected international trade. Narwhals are rarely seen any further south than Greenland, and therefore they were hunted only by Scandinavian whalers. These canny sea-hunters kept the secret of the strange whale’s existence for nearly five hundred years, protecting their supply while they sold the tusks as unicorns’ horns. By the sixteenth century, many Europeans knew that there existed a “sea unicorn,” but knew little else about it; by then, a narwhal’s tusk was worth several times its weight in gold.

Most of the “unicorn’s horns” on the European market were actually the tusks of the narwhal, a whale that grows one long, twisted tooth resembling a horn. Through the demand for narwhal tusks, the unicorn belief affected international trade. Narwhals are rarely seen any further south than Greenland, and therefore they were hunted only by Scandinavian whalers. These canny sea-hunters kept the secret of the strange whale’s existence for nearly five hundred years, protecting their supply while they sold the tusks as unicorns’ horns. By the sixteenth century, many Europeans knew that there existed a “sea unicorn,” but knew little else about it; by then, a narwhal’s tusk was worth several times its weight in gold.

Because of the widespread belief in the healing horn, from the Middle Ages until the eighteenth century, the unicorn was the most common and recognizable symbol of an apothecary or pharmacy. Apothecaries had elaborate signs shaped like unicorns, some of them made with narwhal tusks. Others kept the tusks hanging above the door where patients could see them, as a way of assuring them that they had the real thing. Some pharmacy tusks still survive, including at the famous “White Unicorn” Pharmacy at Klatovy, Czech Republic, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

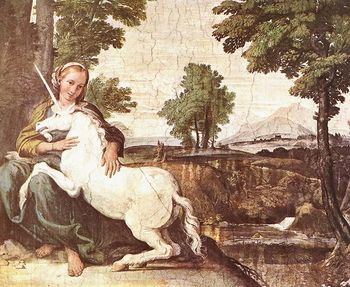

Apart from the crucial belief in the healing horn, three stories about unicorns came to be particularly popular in medieval times. The first was that the unicorn could only be captured with the help of a chaste young virgin. This idea was expressed in the loose assemblage of animal lore called the Physiologus, or later, the Bestiary. Compiled during late antiquity and popular throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, the Physiologus was rewritten and translated many times, so it existed in many versions. One gave the tale this way: “The monoceras, that is, the unicorn, has this nature: he is a small animal like the kid, is exceedingly shrewd, and has one horn in the middle of his head. The hunter cannot approach him because he is extremely strong. How then do we hunt the beast? Hunters place a chaste virgin before him. He bounds forth into her lap and she warms and nourishes the animal and takes him into the palace of kings.” (Physiologus p. 51) Because of its association with virgins, the unicorn was often a symbol of chastity.

Apart from the crucial belief in the healing horn, three stories about unicorns came to be particularly popular in medieval times. The first was that the unicorn could only be captured with the help of a chaste young virgin. This idea was expressed in the loose assemblage of animal lore called the Physiologus, or later, the Bestiary. Compiled during late antiquity and popular throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, the Physiologus was rewritten and translated many times, so it existed in many versions. One gave the tale this way: “The monoceras, that is, the unicorn, has this nature: he is a small animal like the kid, is exceedingly shrewd, and has one horn in the middle of his head. The hunter cannot approach him because he is extremely strong. How then do we hunt the beast? Hunters place a chaste virgin before him. He bounds forth into her lap and she warms and nourishes the animal and takes him into the palace of kings.” (Physiologus p. 51) Because of its association with virgins, the unicorn was often a symbol of chastity. However, the unicorn was also sometimes portrayed as a sexual beast. In a version of the virgin-capture story from the Syriac variant of the Physiologus, “they lead forth a young virgin, pure and chaste, to whom, when the animal sees her, he approaches, throwing himself upon her. Then the girl offers him her breasts, and the animal begins to suck the breasts of the maiden and to conduct himself familiarly with her.” (Shepard p. 49) In an interesting reversal of this idea, the French Arthurian romance The Knight of the Parrot features a female unicorn that suckles a human baby along with her own litter; the result is that the baby grows into a giant. These are not the only contexts in which the unicorn seems to be a sexual beast. Unicorns are also often shown in medieval art in conjunction with naked “wild men” and “wild women,” which is suggestive of sexuality. And most explicitly of all, Rabelais says that a unicorn’s horn is usually limp, “like a turkey-cock’s comb. When an unicorn has a mind to fight or put it to some other use, what does it do but make it stand, and then ‘tis straight as an arrow.” (Rabelais p. 343)

However, the unicorn was also sometimes portrayed as a sexual beast. In a version of the virgin-capture story from the Syriac variant of the Physiologus, “they lead forth a young virgin, pure and chaste, to whom, when the animal sees her, he approaches, throwing himself upon her. Then the girl offers him her breasts, and the animal begins to suck the breasts of the maiden and to conduct himself familiarly with her.” (Shepard p. 49) In an interesting reversal of this idea, the French Arthurian romance The Knight of the Parrot features a female unicorn that suckles a human baby along with her own litter; the result is that the baby grows into a giant. These are not the only contexts in which the unicorn seems to be a sexual beast. Unicorns are also often shown in medieval art in conjunction with naked “wild men” and “wild women,” which is suggestive of sexuality. And most explicitly of all, Rabelais says that a unicorn’s horn is usually limp, “like a turkey-cock’s comb. When an unicorn has a mind to fight or put it to some other use, what does it do but make it stand, and then ‘tis straight as an arrow.” (Rabelais p. 343)

The second influential unicorn tale incorporates the healing horn idea, but fleshes it out into a specific story. It is recounted in the Greek versions of the Physiologus, and only gradually came to be known in the west; by the Late Middle Ages we find it well represented in western European art and literature. In this story, a serpent poisons a well or stream, so that the other animals are unable to drink. The unicorn arrives, dips his horn into the water, and thus counteracts the poison, making the water safe to drink.

The second influential unicorn tale incorporates the healing horn idea, but fleshes it out into a specific story. It is recounted in the Greek versions of the Physiologus, and only gradually came to be known in the west; by the Late Middle Ages we find it well represented in western European art and literature. In this story, a serpent poisons a well or stream, so that the other animals are unable to drink. The unicorn arrives, dips his horn into the water, and thus counteracts the poison, making the water safe to drink. The virgin-capture and the poisoned pool are both illustrated in the “Unicorn Tapestries,” a magnificent series of late medieval wall-hangings probably woven in Brussels, and now on display at the Cloisters Museum in New York. The second tapestry in the series shows the unicorn dipping its horn in the stream to counteract the poison, while other animals such as leopards, weasels, stags, dogs, and rabbits all look on.

The fifth tapestry, which now exists only as two small fragments, shows the unicorn with a young maiden, who is gesturing to a huntsman; the huntsman is blowing his horn, and one of his dogs is leaping on the unicorn. The fragmentary nature of the tapestry confuses matters; there is a dainty hand on the mane of the unicorn that does not belong to the gesturing maiden, so apparently there are two maidens with the unicorn; one keeps the unicorn’s attention while the other betrays him to the hunt. (This was not unheard of in the legend; no less a person than the famed abbess Hildegarde von Bingen suggested using more than one virgin in the capture of a unicorn.) The rich tapestry series is a good indication that these very popular stories had become part of everyday knowledge about unicorns in late medieval Europe.

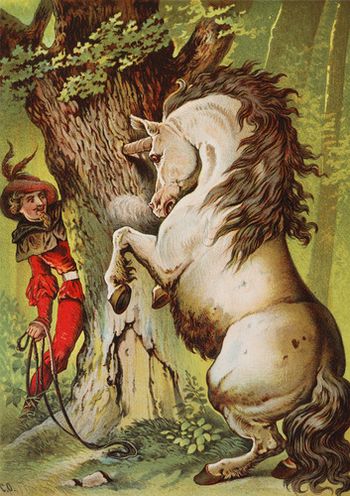

A third medieval story about the unicorn concerns its relationship with the lion. It seems to derive from the “Letter of Prester John,” a document purporting to be from the court of a Christian king in Ethiopia. The letter, which dates to about 1165, claims that the unicorn and the lion are natural enemies, and that the lion kills the unicorn by a subtle ruse: it positions itself between the unicorn and a tree, and when the unicorn charges, it leaps aside. The unicorn’s horn is thus plunged into the tree, and the unicorn cannot withdraw it. The unicorn is trapped, and the lion easily kills it.

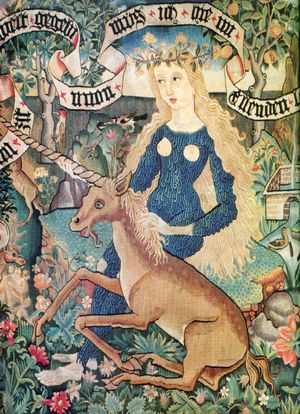

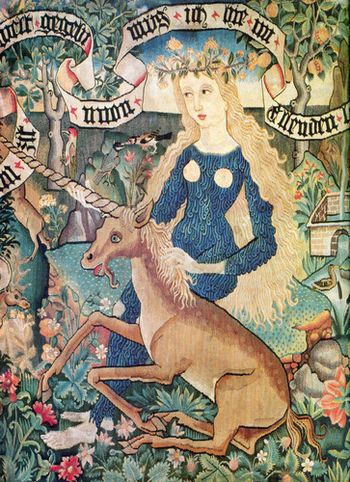

This tale, too, entered folklore, sometimes as a general association of the unicorn with the lion, sometimes as a memory of their great rivalry, and other times as a specific method of killing or capturing unicorns. The association between the animals is clear in another celebrated series of unicorn tapestries, known as “The Lady and the Unicorn,” and currently on display at the Cluny museum in Paris. In these, a lady is attended by a number of animals, including birds, rabbits, and a tame monkey, but the largest and most important are a lion and a unicorn.

The rivalry between the two animals came to be particularly important in Britain, where the lion came to represent England and the unicorn Scotland. An English nursery rhyme, perhaps bearing an echo of Prester John’s letter, runs:

The lion and the unicorn were fighting for the crown.

The lion and the unicorn were fighting for the crown.The lion beat the unicorn all around the town.

Some gave them white bread and some gave them brown;

Some gave them plum cake and drummed them out of town.

The Baring-Goulds, editors of The Annotated Mother Goose, point out the great antiquity of the lion-unicorn rivalry. With the ascension of the Scottish monarch James I to the throne of England in 1603, this rivalry in a British context was reconciled (at least officially), and the lion and unicorn appear as supporters of the shield on the Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom.

The lion’s specific method of killing the unicorn in the Prester John text also remained well known in both learned and popular circles. Spenser tells the story in full, thus:

Like as a Lyon whose imperial powre

Like as a Lyon whose imperial powre A proud rebellious Unicorn defyes,

T'avoid the rash assault and wrathful stowre

Of his fiers foe, him to a tree applyes,

And when him ronning in full course he spyes

He slips aside: the whiles that furious beast

His precious horne, sought of his enemyes,

Strikes in the stocke, ne thence can be releast….

--(Faerie Queen, Book ii, Canto v, Stanza 10)

Shakespeare alludes to it several times; most famously in a line from Act II, scene i of Julius Caesar: “He loves to hear that unicorns may be betrayed with trees.” The idea turns up in eighteenth-century German oral tradition in the tale of the “Brave Little Tailor,” collected by the Brothers Grimm, in which the tailor uses the same ruse to capture a unicorn. In the southern mountains of the United States, the folktale hero Jack catches unicorns the same way, for example in both Ray and Orville Hicks’s versions of “Jack and the Varmints.”

How ancient are these medieval unicorn beliefs? Odell Shepard has pointed out that the ancient city of Persepolis, built in about 515 B.C., contains friezes and reliefs that were probably copies of even older Babylonian sources. Several of these appear to show a lion and a one-horned animal locked in combat. Furthermore, both Brown and Shepard point to the “three-legged ass,” a fantastic creature from the Bundahishn, or Zoroastrian creation myth, which is clearly said to have one horn, and to purify the waters with that horn, in order to undo the poison placed there by servants of evil. Because this text was compiled in the 7th century AD, but reflects ideas at least a thousand years older, it is hard to date each idea precisely. However, given that Zoroastrianism is Persian, and that Ctesias wrote the Indica in Persia, it seems likely that his “Indian ass” was based on some version of this myth, which was already old in Ctesias’s day.

An Ark, a Schmendrick, and a Fallen Star: The Modern Unicorn.

As we’ve already seen, the unicorn didn’t die out in the middle ages, but continues to roam through our literature, art and culture. Some tales exist in different versions, as modern folklore. One example is the story that unicorns died out because they literally “missed the boat” when Noah was loading the Ark: it has been told by C.S. Lewis in a 1948 poem, by Edward D. Hoch in a 1958 short story, by Shel Silverstein in a 1962 song, and by Geraldine McCaughrean in a 1997 children’s book. In each of these variants, the reason the unicorn misses the boat is different. In Lewis’s, Noah’s lazy son Ham refuses to let the unicorn aboard, and Noah’s lament for the beast draws parallels between the unicorn and Christ: “O noble and unmated beast, my sons were all unkind/In such a night what stable and what manger will you find?” In the Hoch story, the greed of the unicorns’ owner prevents Noah’s son Shem from buying the beasts. In the Silverstein song (a #7 chart hit for the Irish Rovers in 1968), the unicorns are foolish and playful, and fail to enter the Ark in time. In the McCaughrean book, the unicorns are too noble, and spend too much time helping the other animals.

As we’ve already seen, the unicorn didn’t die out in the middle ages, but continues to roam through our literature, art and culture. Some tales exist in different versions, as modern folklore. One example is the story that unicorns died out because they literally “missed the boat” when Noah was loading the Ark: it has been told by C.S. Lewis in a 1948 poem, by Edward D. Hoch in a 1958 short story, by Shel Silverstein in a 1962 song, and by Geraldine McCaughrean in a 1997 children’s book. In each of these variants, the reason the unicorn misses the boat is different. In Lewis’s, Noah’s lazy son Ham refuses to let the unicorn aboard, and Noah’s lament for the beast draws parallels between the unicorn and Christ: “O noble and unmated beast, my sons were all unkind/In such a night what stable and what manger will you find?” In the Hoch story, the greed of the unicorns’ owner prevents Noah’s son Shem from buying the beasts. In the Silverstein song (a #7 chart hit for the Irish Rovers in 1968), the unicorns are foolish and playful, and fail to enter the Ark in time. In the McCaughrean book, the unicorns are too noble, and spend too much time helping the other animals.This story, too, may have its basis in older traditions. There is a section of the Jewish Talmud (p. 23) describing the difficulties Noah had loading an animal called the orzila into the Ark; it is thought that the orzila is the same as the re’em, and once again, it has often been translated as “unicorn.” Although in the Talmudic tale the animal does not perish (he is lashed to the ark by his horn and survives), it is just possible that the Talmud lies at the origin of the multifaceted legend of Noah and the unicorn.

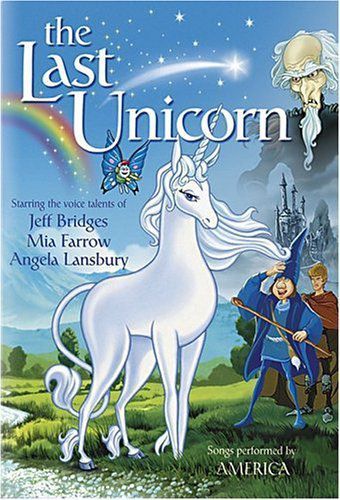

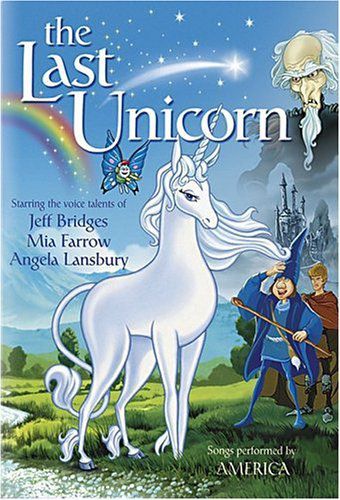

Probably the best-loved modern fantasy work featuring unicorns is Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn. Set in a medieval fairy tale realm, the novel tells the story of a unicorn who learns that the others of her kind have disappeared, and who sets out to find and free them. Beagle recounts many traditional unicorn stories, including the virgin-capture. His unicorn wields the traditional healing horn, which can even revive the dead. Beagle’s unicorn fights a magical Red Bull, who has driven all the other unicorns into the sea, and this carries echoes of the traditional lion-combat. At the same time, the story is a coming-of-age tale for Prince Lir, who is young, and for the Unicorn, Schmendrick the Magician, and Molly Grue, who are not; all four characters must sacrifice, learn and grow. The animated film version presents a simpler version of the story, but is notable for beautiful images of unicorns based on medieval tapestries and illuminated manuscripts. In addition to The Last Unicorn, Beagle has published “Two Hearts,” a sequel that reveals the fate of Lir, Schmendrick, Molly, and the Unicorn. He has also written The Unicorn Sonata, set in a different world and featuring a different kind of unicorn; “Julie’s Unicorn,” a story about Beagle’s popular character Joe Farrell, featuring a miniature unicorn; and The Last Unicorn: The Lost Version, which was his first, abandoned attempt to write what became his most popular novel.

Probably the best-loved modern fantasy work featuring unicorns is Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn. Set in a medieval fairy tale realm, the novel tells the story of a unicorn who learns that the others of her kind have disappeared, and who sets out to find and free them. Beagle recounts many traditional unicorn stories, including the virgin-capture. His unicorn wields the traditional healing horn, which can even revive the dead. Beagle’s unicorn fights a magical Red Bull, who has driven all the other unicorns into the sea, and this carries echoes of the traditional lion-combat. At the same time, the story is a coming-of-age tale for Prince Lir, who is young, and for the Unicorn, Schmendrick the Magician, and Molly Grue, who are not; all four characters must sacrifice, learn and grow. The animated film version presents a simpler version of the story, but is notable for beautiful images of unicorns based on medieval tapestries and illuminated manuscripts. In addition to The Last Unicorn, Beagle has published “Two Hearts,” a sequel that reveals the fate of Lir, Schmendrick, Molly, and the Unicorn. He has also written The Unicorn Sonata, set in a different world and featuring a different kind of unicorn; “Julie’s Unicorn,” a story about Beagle’s popular character Joe Farrell, featuring a miniature unicorn; and The Last Unicorn: The Lost Version, which was his first, abandoned attempt to write what became his most popular novel.Many modern fantasy authors borrow the medieval lore of the unicorn and weave it deftly into their own stories. Neil Gaiman and Charles Vess, for example, mine medieval folklore quite deeply in their illustrated novel Stardust, including all three of the most popular medieval stories: the combat with the lion, the virgin-capture, and the healing horn. After the hero, Tristran Thorne, saves a unicorn from its enemy the lion, the grateful unicorn lays his head in the lap of Tristran’s virginal companion, the star-maiden Yvaine, and agrees to be their steed.

The unicorn later neutralizes a poisoned cup of wine with his horn and valiantly defends the young couple against an evil witch. In the end the witch kills the beast, beheads him, and eventually saws off his horn for its medicinal value…a sad end for such a noble character. (The film version includes the unicorn briefly, but not his horrible fate.) A similarly gruesome unicorn slaying occurs in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, after Gawaine and his brothers use a virgin to entrap the magical beast.

Other fantasists play at the margins of medieval stories. Lewis Carroll includes the lion and unicorn fighting for the crown in Through the Looking Glass, but whether he knew of the nursery rhyme’s connection with older stories is impossible to say. Tracy Chevalier recounts traditional unicorn lore, slanted through the agendas of her narrators, in The Lady and the Unicorn, a historical novel about the creation of the magnificent Cluny tapestries. Sharan Newman, in Guinevere, plays with the virgin-capture theme by having her unicorn become psychically and emotionally connected to Guinevere; but Newman’s unicorn is pledged to one virgin only, and dies as soon as Guinevere loses her innocence. Theodore Sturgeon, in his classic story “The Silken-Swift,” challenges our notions of innocence by having the unicorn eschew a technically virginal but spiritually corrupt maiden in favor of a young rape victim who is innocent and kind. And C.S. Lewis, rather than borrowing medieval plots, borrows medieval Christian allegorical meanings; in The Last Battle, the noble unicorn Jewel serves the Christ-like figure of Aslan the lion.

Other fantasists play at the margins of medieval stories. Lewis Carroll includes the lion and unicorn fighting for the crown in Through the Looking Glass, but whether he knew of the nursery rhyme’s connection with older stories is impossible to say. Tracy Chevalier recounts traditional unicorn lore, slanted through the agendas of her narrators, in The Lady and the Unicorn, a historical novel about the creation of the magnificent Cluny tapestries. Sharan Newman, in Guinevere, plays with the virgin-capture theme by having her unicorn become psychically and emotionally connected to Guinevere; but Newman’s unicorn is pledged to one virgin only, and dies as soon as Guinevere loses her innocence. Theodore Sturgeon, in his classic story “The Silken-Swift,” challenges our notions of innocence by having the unicorn eschew a technically virginal but spiritually corrupt maiden in favor of a young rape victim who is innocent and kind. And C.S. Lewis, rather than borrowing medieval plots, borrows medieval Christian allegorical meanings; in The Last Battle, the noble unicorn Jewel serves the Christ-like figure of Aslan the lion.  Many authors use unicorns as cosmic symbols of peace, prosperity and order. In Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, a mystical unicorn is the living embodiment of the principle of order, while a serpent embodies chaos, ideas which would seem at home in the pages of the Bundahishn. In the fantasy film Legend, two mated unicorns are the keepers of the world’s light and warmth; when one is killed, the world experiences premature winter, and if the other should be killed, it will cause eternal night. And Madeleine L’Engle’s A Swiftly Tilting Planet introduces powerful, winged, time-traveling unicorns who serve good against evil, peace against war, and joy against despair.

Many authors use unicorns as cosmic symbols of peace, prosperity and order. In Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, a mystical unicorn is the living embodiment of the principle of order, while a serpent embodies chaos, ideas which would seem at home in the pages of the Bundahishn. In the fantasy film Legend, two mated unicorns are the keepers of the world’s light and warmth; when one is killed, the world experiences premature winter, and if the other should be killed, it will cause eternal night. And Madeleine L’Engle’s A Swiftly Tilting Planet introduces powerful, winged, time-traveling unicorns who serve good against evil, peace against war, and joy against despair.In still other works, unicorns have characteristics completely unknown to traditional lore. In Piers Anthony’s Apprentice Adept novels, the unicorns are a bizarre mix of wit and whimsy: they are intelligent, multicolored shape-changers, and can play music with their horns. In Roger Zelazny’s “The Unicorn Variations,” the unicorn lives in a dimension filled with mythical creatures like griffins and bigfoots, is very adept at chess, and loves a cold beer. Bruce Coville’s Unicorn Chronicles feature intelligent unicorns who have a land and a society of their own. And, of course, dozens of other fantasy classics, including Robert Asprin’s Myth series, Terry Brooks’s Landover novels, and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, feature unicorns as supporting characters or generic “magical creatures.”

What is the future of the unicorn? Unless we discover unicorns on another planet, as The Three Stooges did, in the film Have Rocket, Will Travel; unless we create unicorns through genetic engineering, as in Vonda MacIntyre’s “Elfleda” or Gene Wolfe’s “The Woman the Unicorn Loved”; unless we discover, in the forests of Vietnam, a one-horned version of the Pseudoryx nghetinhensis; can the unicorn still have any place in our future?

Of course it can. What is the unicorn but the Holy Grail of animals, to be sought by all but found by few? If there are things worth having faith in, why not the unicorn? As Edward Topsell put it in his 1607 bestiary, “God himself must needs be traduced, if there is no unicorn in the world.”

Or better yet, as Lewis Carroll’s unicorn said to Alice, “...if you'll believe in me, I'll believe in you. Is that a bargain?”

Further Reading, Listening and Viewing

Books: History and Scholarship

Aristotle. History of Animals. Ed. and trans. by Richard Cresswell. London: George Bell and Sons, 1883.

Aristotle. History of Animals. Ed. and trans. by Richard Cresswell. London: George Bell and Sons, 1883.Aelian. On the Characteristics of Animals. Ed. and trans. by A. F. Scholfield. 3 vols. Loeb Classical Library. London: Heinemann, 1958.

Baring-Gould, William S. and Ceil. The Annotated Mother Goose. New York: Meridian, 1967.

Bingen, Hildegarde. Physica. Ed. and trans. by Priscilla Throop. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press, 1998.

Brown, Robert. The Unicorn: A Mythological Investigation. London: Spottswoode & Co., 1881.

Caesar, Caius Julius. The Gallic War. Ed. by J. B. Greenough, Benjamin L. D'Ooge, and M. Grant Daniell. Boston: Ginn & Co., 1898.

Ctesias. “Indica,” in The Library of Photius, ed. and trans. by J.H. Freese. New York: MacMillan, 1920.

Freeman, Margaret B. The Unicorn Tapestries. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.

Hathaway, Nancy. The Unicorn. New York: Avenel Books, 1984.

Johnsgard, Paul A. and Karin. Dragons and Unicorns: A Natural History. New York: MacMillan, 1992.

Lindahl, Carl, John McNamara and John Lindow, eds. Medieval Folklore. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Physiologus. Ed. and trans. by Michael J. Curley. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Ed and trans. by John Bostock and H.T. Riley. London: H.G. Bohn, 1855.

Shepard, Odell. The Lore of the Unicorn. New York: Harper Colophon, 1979.

The Talmud. Ed. and trans. by Joseph Barclay. London: John Murray, 1878.

Topsell, Edward. The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents and Insects. New York: Da Capo Press, 1967.

Books: Fiction and Folklore

Anthony, Piers. Split Infinity. New York: Del Ray, 1980.

Asprin, Robert. Another Fine Myth. New York: Dell, 1979.

Brooks, Terry. The Black Unicorn. New York: Del Ray, 1987.

Beagle, Peter S. “Julie’s Unicorn” in The Rhinoceros who Quoted Nietszche. San Francisco: Tachyon Publications, 1997.

Beagle, Peter S. The Last Unicorn. New York: Viking Press, 1968.

Beagle, Peter S. “Two Hearts.” Available as a free download from www.peterbeagle.com

Beagle, Peter S. The Unicorn Sonata. London: Headline, 1996.

Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1954.

Chevalier, Tracy. The Lady and the Unicorn. New York: Dutton, 2004.

Coville, Bruce. The Unicorn Chronicles. New York: Scholastic, 2005.

Escehenbach, Wolfram Von. Parzival. Ed. and trans. by Helen M. Mustard and Charles E. Passage. New York: Vintage, 1961.

Gaiman, Neil and Charles Vess. Stardust. New York: Vertigo/D.C. Comics, 1998.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Ed. and trans. by Jack Zipes. New York: Bantam, 1987.

Hicks, Orville. “Jack and the Varmints” in Jack Tales and Mountain Yarns as Told by Orville Hicks. Boone, North Carolina: Parkway, 2009.

Hoch, Edward D. “The Last Unicorns” in 100 Great Fantasy Short Short Stories, ed. by Isaac Asimov, Terry Carr, and Martin H. Greenberg. New York: Avon, 1984.

“Knight of the Parrot, The.” Ed. and Trans. by Thomas E. Vesce. In The Romance of Arthur, vol. III. Ed. by James J. Wilhelm. New York: Taylor and Francis, 1988.

L’Engle, Madeleine. A Swiftly Tilting Planet. New York: Dell, 1978.

Lewis, C. S. The Chronicles of Narnia. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

Lewis, C.S. “The Sailing of the Ark.” Punch 215 (11 Aug 1948): 124. (published under the pseudonym Nat Whilk)

McCaughrean, Geraldine. Unicorns! Unicorns! New York: Holiday House, 1997.

McIntyre, Vonda. “The Woman the Unicorn Loved,” in Dann and Dozois, 1982.

Newman, Sharan. Guinevere. New York: Bantam, 1982.

Rabelais, Francois. Gargantua and Pantagruel. Ed. and trans. by Sir Thomas Urquhart and Peter le Motteux. London: David Nutt, 1900.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter: The Complete Series. New York: Scholastic, 2009.

Shakespeare, William. The Riverside Shakespeare. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1996.

Spenser, Edmund. Edmund Spenser’s Poetry. New York: W. W. Norton, 1993.

Sturgeon, Theodore. “The Silken-Swift” in Dann and Dozois, 1982.

White, T.H. The Once and Future King. London: Collins, 1958.

Wolfe, Gene. “Elfleda,” in Dann and Dozois, 1982.

Zelazny, Roger. The Great Book of Amber. New York: Avon Eos, 1999.

Zelazny, Roger. “The Unicorn Variations” in Dann and Dozois, 1982.

Books: Fiction Anthologies

Coville, Bruce, ed. The Unicorn Treasury. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

Dann, Jack and Gardner Dozois, ed. Unicorns! New York: Ace, 1982.

Dann, Jack and Gardner Dozois, ed. Unicorns II. New York: Ace, 1992.

Beagle, Peter S., Janet Berliner, and Martin H, Greenberg, eds. Peter S. Beagle’s Immortal Unicorn. New York: HarperPrism, 1995.

Recordings

Hicks, Ray. Ray Hicks Tells Four Traditional Jack Tales. Sharon, Connecticut: Folk-Legacy Records, 1977.

The Irish Rovers. The Unicorn. New York: MCA Records, 1967.

Films/DVDs

Have Rocket, Will Travel, VHS. Directed by Lowell Rich. Hollywood: Columbia Pictures, 1959.

The Last Unicorn, DVD. Directed by Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass. Santa Monica: Lion’s Gate Entertainment, 1982.

Legend, DVD. Directed by Ridley Scott. Universal City: Universal Studios, 1985.

Stardust, DVD. Directed by Matthew Vaughn. Hollywood: Paramount Pictures, 2007.

Gallery with Captions

Believing in Unicorns

From a 1566 manuscript of a bestiary by Manuel Philes (Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris, ms. 3401), this illustration of a unicorn follows Ctesias's description, as it came down through Aelian and Pliny to the Middle Ages.

An etching by Sidney Hall showing several constellations, including Monoceros the Unicorn. This was an illustration in Jehosaphat Aspin's A Familiar Treatise on Astronomy..., from 1825. Library of Congress.

This painting by Raphael was done in about 1506. The small size of the unicorn is explained by the fact that Raphael apparently originally painted a lap-dog, and later replaced it by painting it over with a unicorn. Later still, a St. Catherine's Wheel was painted over the unicorn. The unicorn was revealed by restoration in the 1930s, and the underlying dog was discovered in the 1950s.

This tapestry fragment, showing a naked wild woman and a unicorn, dates to about 1500. It was used as a chair-back cover in Alsace, on the Upper Rhine. It is currently in the historical Museum of Basel

This engraving shows a unicorn cleaning a poisoned pool with its horn. Serpents, the traditional poisoners of the water, can be seen fleeing from the unicorn.

This tapestry, currently at the Cloisters Museum in New York, was woven in Belgium in about 1500. It shows the unicorn healing a poisoned stream with its horn, while other animals, as well as the encroaching hunting-party, look on.

"À mon seul désir" is the sixth and last of a series of tapestries designed in France and woven in Flanders in the late 15th century. It has been interpreted as representing love or understanding; the other five in the series represent the five senses. Each of the six tapestries depicts a noble lady with the unicorn on her left and a lion on her right; some include a monkey as well.

This illustration by Carl Offterdinger (1829-1889) was for “The Valiant Little Tailor.” It shows one traditional way to capture or kill a unicorn: getting the beast to ram its horn into a tree.

LP jacket for The Unicorn by The Irish Rovers. The title track, a song written by Shel Silverstein, went to number 7 on the charts.

Charles Vess's illustration of the fight between the lion and the unicorn, from Stardust. © Charles Vess; all rights are reserved by Charles Vess.

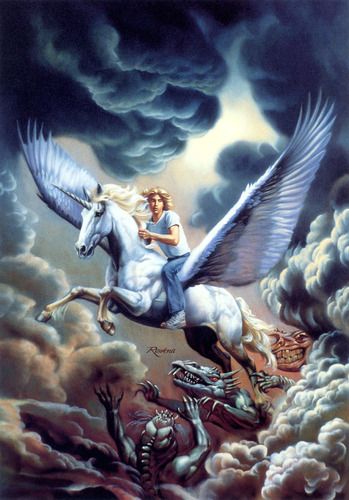

Cover art for L'Engle's A Swiftly Tilting Planet, showing Charles Wallace Murray riding the winged unicorn Gaudior. The painting is by Rowena Morrill.

Steve Winick at the sign for The Unicorn Bookshop in Trappe, Maryland. Photo by Jennifer Cutting.