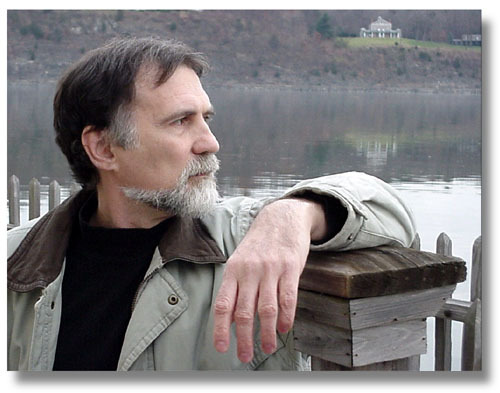

Robert M. Place

Artist, Mystic, Scholar: Robert M. Place

By Stephen D. Winick

(Originally Appeared in Tarot World Magazine, 2009)

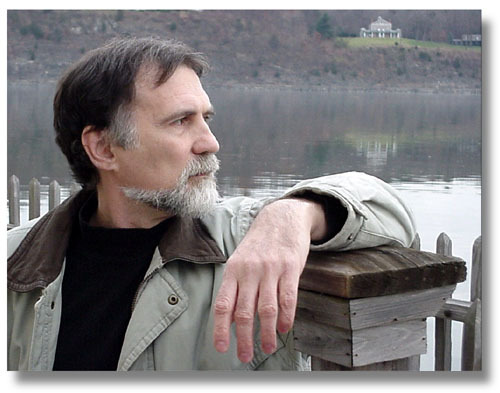

Robert M. Place is a rarity in the world of Tarot. He is one of the most articulate commentators on the deck’s history, and one of the most meticulous researchers into its meaning. But he is, first and foremost, a visual artist. His unique ability to understand the cards, to explicate them, and to read them, is undoubtedly an extension of his artistic talent and training. In this regard, he joins a select handful of artists who have contributed mightily, not only to the creation of new decks, but to the understanding of old ones. “It’s artists who created the Tarot,” Place reminded me in a May, 2008 interview. “It’s first and foremost a work of art.”

Place has known he was an artist since early childhood. “When I first picked up a crayon,” he said, “I knew, this is it!” Always precocious, he was drawing true-to-life representations of what he saw by the age of seven. He also practiced constantly, bringing his sketch pad everywhere. He recalled a field trip to a colonial house associated with George Washington. Outside, a painter had set up his easel. “While all the other kids were checking out the house, and the woods, I was standing there watching the painter!”

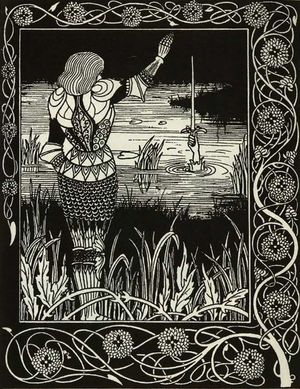

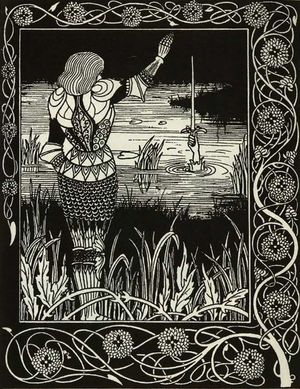

Although the first art movement he can remember studying was surrealism, Place was soon more taken with several schools that had predated the surrealists: the Pre-Raphaelites, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones; Symbolism, including John William Waterhouse; and Art Nouveau, which included Aubrey Beardsley. When he was in high school, these movements were out of vogue, Place remembered. But in the late 60s, when he was in college, they were rediscovered. “I remember there was a big retrospective of Aubrey Beardsley at the Huntington Hartford museum in New York. And there started to be all these books on the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolists. And I was avidly collecting all these books, and going to museums to see all these artworks, and learning about Burne-Jones and Rossetti, which anyone can see is a big influence on my work.” In addition, he began to study Renaissance art, and to try his hand at copying it—another clear influence on his later work.

Although the first art movement he can remember studying was surrealism, Place was soon more taken with several schools that had predated the surrealists: the Pre-Raphaelites, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones; Symbolism, including John William Waterhouse; and Art Nouveau, which included Aubrey Beardsley. When he was in high school, these movements were out of vogue, Place remembered. But in the late 60s, when he was in college, they were rediscovered. “I remember there was a big retrospective of Aubrey Beardsley at the Huntington Hartford museum in New York. And there started to be all these books on the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolists. And I was avidly collecting all these books, and going to museums to see all these artworks, and learning about Burne-Jones and Rossetti, which anyone can see is a big influence on my work.” In addition, he began to study Renaissance art, and to try his hand at copying it—another clear influence on his later work.

Place’s attention to historical styles brought him into contact with two things that would resonate deeply through his Tarot art: saints and mystical experience. Both came to him through his work with Russian painters of icons, stylized paintings of Orthodox saints. This began one summer, when he accompanied a Russian friend to a monastery in upstate New York where the monks were famed artists. “They would put gold leaf down by taking wads of monks’ bread and pounding it on the gold, and pounding it into the gum that they had already painted on the surface,” he remembered. “So they were basically using medieval techniques.” It was those techniques that fascinated Place, and he began to learn them himself, traveling to the monastery several more times for further study.

Place’s attention to historical styles brought him into contact with two things that would resonate deeply through his Tarot art: saints and mystical experience. Both came to him through his work with Russian painters of icons, stylized paintings of Orthodox saints. This began one summer, when he accompanied a Russian friend to a monastery in upstate New York where the monks were famed artists. “They would put gold leaf down by taking wads of monks’ bread and pounding it on the gold, and pounding it into the gum that they had already painted on the surface,” he remembered. “So they were basically using medieval techniques.” It was those techniques that fascinated Place, and he began to learn them himself, traveling to the monastery several more times for further study.

While studying with the monks, he became aware that, as he put it, “the paintings themselves were magical.” He experienced this himself, while looking at an icon of Boris and Gleb, the earliest Russian saints. “The panel was split between the two brothers,” he said. “One had his right hand up and his left hand down, and the other had his left hand up and his right hand down. One had a red inner garment and a blue outer garment, and the other a blue inner garment and red outer garment. It created this duality that kept being reconciled by the two. I kept looking back and forth, from one side to the other, and this wave of energy came off the icon, and just blasted into me. The rest of the day, I was in this incredible high state, where everything was incredibly beautiful, and I just wandered around the monastery, awestruck.”

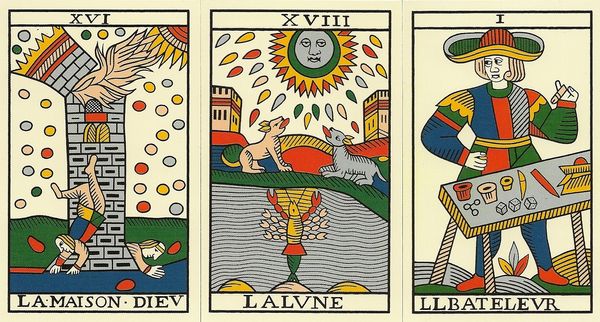

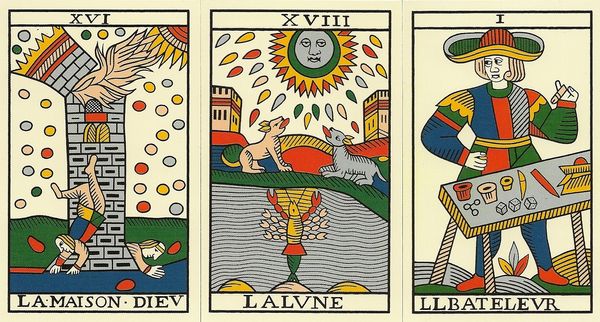

Art, sacredness and mysticism…all seemed to be in position for Place’s rendezvous with the Tarot. Although in college he had been aware of the Tarot through his studies of esoteric art, had sketched four cards of a deck based on the Tarot of Marseilles, and had dated a woman who read Tarot, he hadn’t gotten deeply involved at the time. But later, in 1982, when he and his wife Rose Ann had established a business making jewelry, the Tarot magically entered his life, through a dream.

Place dreamed that he was in a building, and a phone rang. He picked it up, and a dream operator connected him to a secretary with a law firm. She told him he had an inheritance coming from an ancestor in England. She could not tell him what it was, but he would know it when he saw it. She said it came with a karmic debt incurred by his ancestor, who had misused it in some way. She also told him it would come in a box, and it was called “the key.” Place agreed to accept the gift, and the debt that came with it.

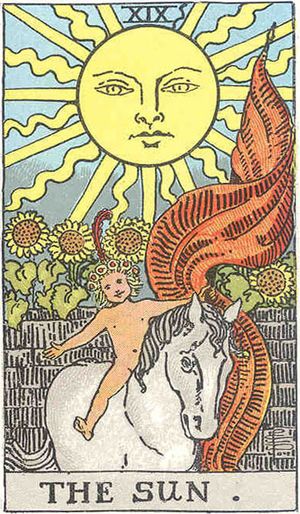

“The dream was so vivid that I just expected that when I woke up, the box would be there at the foot of the bed,” he marveled. “That was a bit naïve, but considering what happened later, it wasn’t that naïve. Because within days, my friend Scott came over, with the Waite-Smith deck that he’d just received in the mail. As he walked in the door, my head turned involuntarily, and my eyes focused on the deck, and I instantly recognized that that was the thing from England. It comes in a box, it was first published in England, the original book [that described it] was Key to the Tarot, the trumps were called keys…I said, ‘oh, of course, it’s the Tarot!’ It was so obvious, as soon as I saw it!” Within a few more days, another friend who had an extra Marseilles deck came to visit Place and said, “I thought you needed a Tarot deck.” Soon after that, he bought his own Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, and the inheritance was complete.

“The dream was so vivid that I just expected that when I woke up, the box would be there at the foot of the bed,” he marveled. “That was a bit naïve, but considering what happened later, it wasn’t that naïve. Because within days, my friend Scott came over, with the Waite-Smith deck that he’d just received in the mail. As he walked in the door, my head turned involuntarily, and my eyes focused on the deck, and I instantly recognized that that was the thing from England. It comes in a box, it was first published in England, the original book [that described it] was Key to the Tarot, the trumps were called keys…I said, ‘oh, of course, it’s the Tarot!’ It was so obvious, as soon as I saw it!” Within a few more days, another friend who had an extra Marseilles deck came to visit Place and said, “I thought you needed a Tarot deck.” Soon after that, he bought his own Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, and the inheritance was complete.

Early on, Place tried to learn about Tarot by reading books. From his own studies in art history, however, he found many of the historical claims in books unlikely. Instead, he decided to learn from the pictures. With long experience in reading pictures, he discovered much of the esoteric information encoded into the cards by Waite, and by the generations of Tarot creators before him. From broad correspondences, such as that of the four elements with the four suits, to individual plant and animal symbols, Place was able to read the cards with ease. Beginning with the Celtic Cross layout, Place soon found himself dissatisfied with its limitations. He created his own method of reading involving several groups of three cards, which he teaches to this day. For years, he did Tarot readings for free, for anyone who asked, as a way of discharging the karmic debt that had come with his cards.

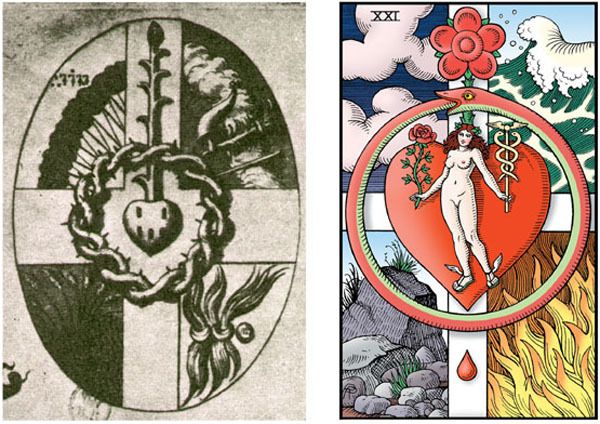

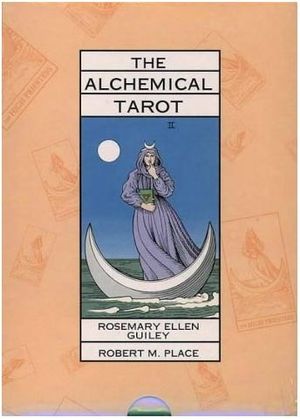

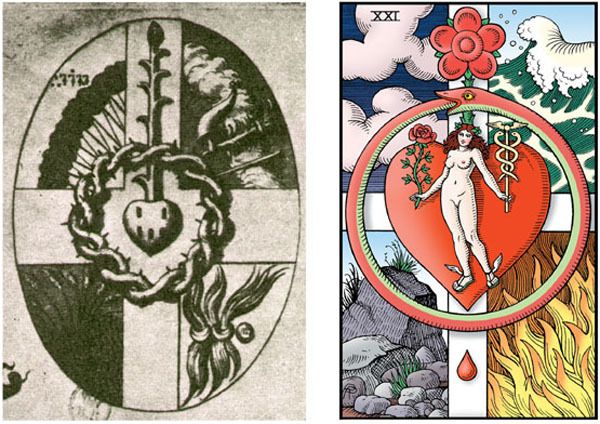

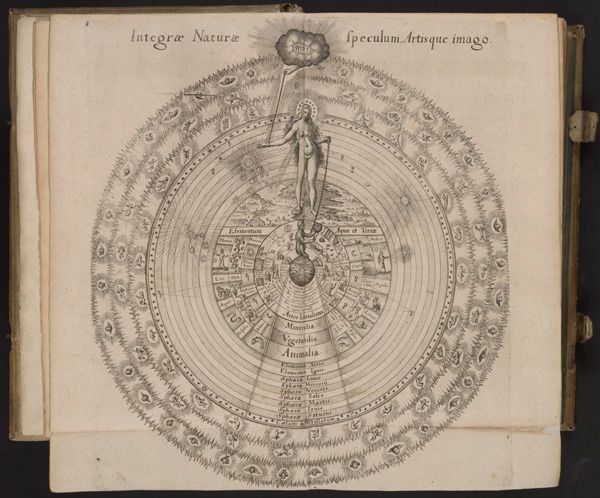

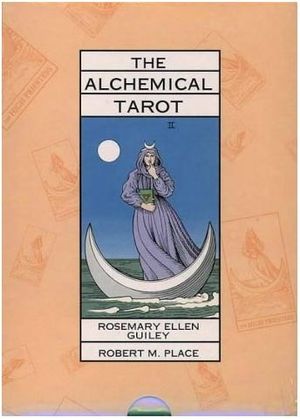

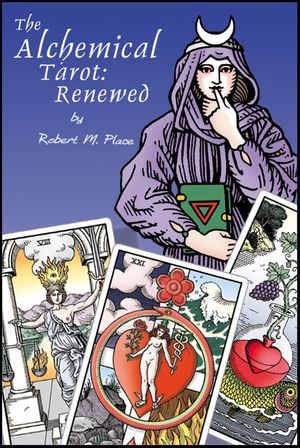

“It’s like it opened some secret door in my brain,” Place said. He stepped through that door, and found himself designing his first deck, The Alchemical Tarot. He began by further researching alchemical images, including C. G. Jung’s use of alchemical symbolism in Psychology and Alchemy. Then he began the illustrations, using several methods to devise his card concepts. “I was trying to understand the cards as they originally were understood in the Renaissance,” he explained. “I looked though many different alchemical images to see how they fit, and sometimes I took aspects of several different alchemical images, and put them together with certain Tarot aspects.” Thus, his World card borrows aspects of the alchemical design for the Philosopher’s Stone, but also includes the Ouroboros, a common alchemical motif, and a nude female figure representing the anima mundi, an important figure in Platonic and alchemical thought, who also appears on more traditional World cards.

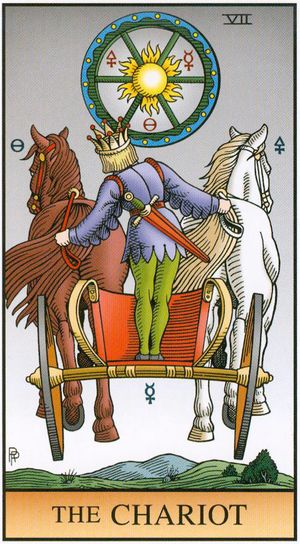

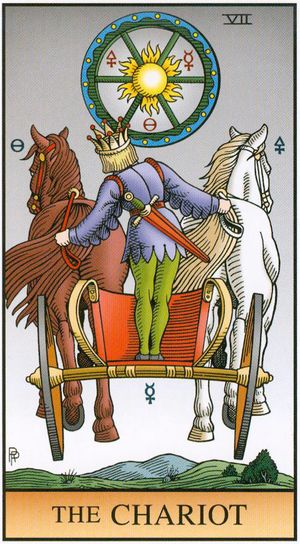

Another approach led to some of the more unusual images in the deck. He adopted the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn’s method of doing guided meditations (or as he now calls them, shamanic journeys) in which he visualized the cards as doors, passed through the doors, and interacted with the characters he found. He included aspects of many of these visions in his card designs. For example, behind the door of the Chariot card, he found a chariot much like the one on more traditional cards, driven by a very youthful driver. The driver turned the chariot around, and invited Place to get on the back with him. The two flew off on a journey together, flying high in the air, to witness a wheel of sunrises in the sky, with larger sun at the center. Place recognized this central sun as the internal sun, an important alchemical concept. Place’s Chariot card reflects this vision: the chariot is turned around, facing away from the observer, who is invited to get aboard; above, the vision of the suns is clearly visible.

Another approach led to some of the more unusual images in the deck. He adopted the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn’s method of doing guided meditations (or as he now calls them, shamanic journeys) in which he visualized the cards as doors, passed through the doors, and interacted with the characters he found. He included aspects of many of these visions in his card designs. For example, behind the door of the Chariot card, he found a chariot much like the one on more traditional cards, driven by a very youthful driver. The driver turned the chariot around, and invited Place to get on the back with him. The two flew off on a journey together, flying high in the air, to witness a wheel of sunrises in the sky, with larger sun at the center. Place recognized this central sun as the internal sun, an important alchemical concept. Place’s Chariot card reflects this vision: the chariot is turned around, facing away from the observer, who is invited to get aboard; above, the vision of the suns is clearly visible.

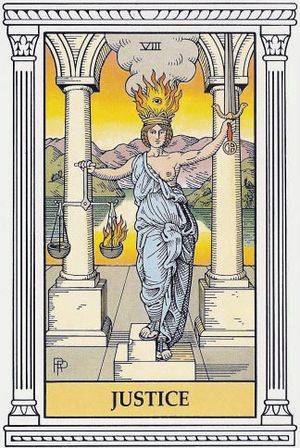

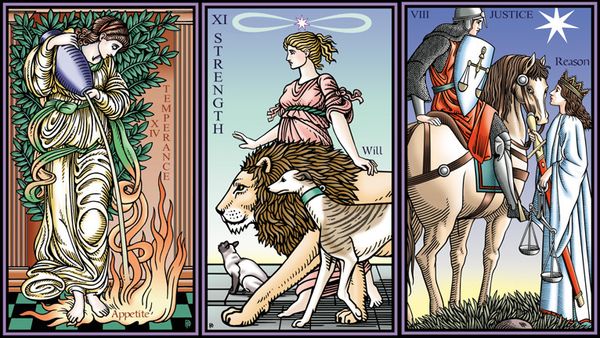

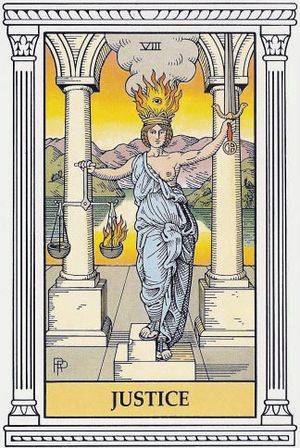

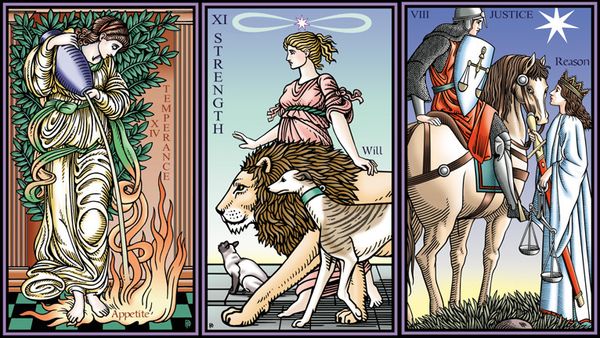

A third card that benefited from Place’s intuition was Justice. At first, he used a Renaissance drawing as a model, added a crown and a pair of scales, and decided that the scales would weigh fire against water, based on alchemical principles. He gave Justice a sword, and on the hilt put the alchemical symbol for vitriol, which had seen in an alchemical design. Place then added fire and smoke coming out of Justice’s crown, and an eye of consciousness in the flames, “totally on a whim,” he said. The figure stood between two columns, with the scales in front of one and the sword in front of the other. As Place looked at the image he had drawn, he recognized two things. First, with the crown of smoke and fire, Justice had become a third and central column. Second, the three-column arrangement resembled the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, in which the left column represents severity, the right column represents mercy, and the central column, representing balance or equilibrium, culminates on top with the crown, and leads to God-consciousness, represented by the eye.

This in turn taught Place some lessons about justice. “The column of mercy is the one with the sword, and severity is the one with the scales,” he observed. “Severity meant that you couldn’t allow your emotions to interfere when you were weighing out things, and tying to find out the truth…you’ve got to be impartial. Whereas mercy, that was the sword, because the sword was punishment.” In Place’s view, then, severity in the search for truth is appropriate, if it is tempered by mercy in the application of punishment. “A lot of people might think it should go the other way,” he said, “but I think that’s the problem! In the United States we have five percent of the world’s population, but twenty-five percent of the world’s prisoners, because we’re so vindictive!”

This in turn taught Place some lessons about justice. “The column of mercy is the one with the sword, and severity is the one with the scales,” he observed. “Severity meant that you couldn’t allow your emotions to interfere when you were weighing out things, and tying to find out the truth…you’ve got to be impartial. Whereas mercy, that was the sword, because the sword was punishment.” In Place’s view, then, severity in the search for truth is appropriate, if it is tempered by mercy in the application of punishment. “A lot of people might think it should go the other way,” he said, “but I think that’s the problem! In the United States we have five percent of the world’s population, but twenty-five percent of the world’s prisoners, because we’re so vindictive!”

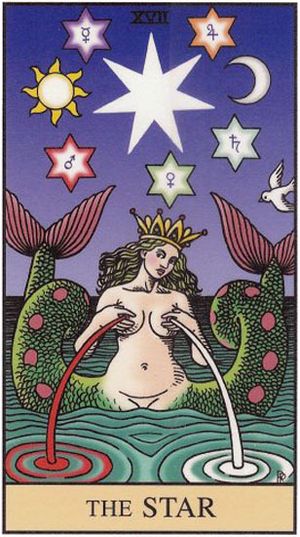

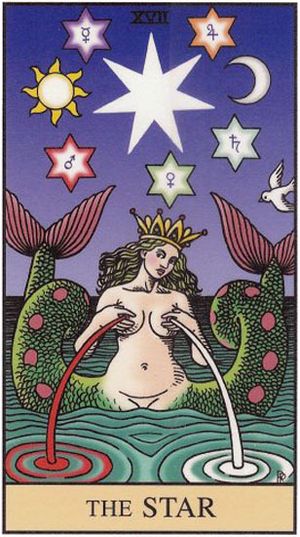

All this journeying, drawing and learning took time. It would be years before Place finished The Alchemical Tarot, during which time, he says, odd synchronicities occurred. He described one in particular, which led to his becoming a writer, and to the publication of The Alchemical Tarot: soon after he began studying Gnosticism, he came across the now-defunct magazine Gnosis in a health food store, while shopping with his wife and his friend Sue. At Sue’s urging, he bought the magazine. He read it, loved it, and subscribed. Soon after that, something told him Gnosis would soon do an issue on the Tarot, and that he should share some of his work. He sent them copies of several of the original drawings, including the Star. A week or so later, he received a phone call from the publisher, Jay Kinney.

While it was not true that Gnosis was planning a Tarot issue, it was true that they had been specifically seeking an illustration of Sophia, goddess of wisdom. Gnosis bought the illustration on Place’s Star card, and also asked Place to write a one-page article on The Star. Both appeared in 1989, in issue 13 of Gnosis, as a sidebar to an article on Sophia by Caitlín Matthews. This was the first piece of writing Place published.

While it was not true that Gnosis was planning a Tarot issue, it was true that they had been specifically seeking an illustration of Sophia, goddess of wisdom. Gnosis bought the illustration on Place’s Star card, and also asked Place to write a one-page article on The Star. Both appeared in 1989, in issue 13 of Gnosis, as a sidebar to an article on Sophia by Caitlín Matthews. This was the first piece of writing Place published.

The sidebar and illustration came to the attention of Rosemary Ellen Guiley, who was working on her book The Mystical Tarot. She contacted Place, and asked him for several more illustrations, with brief write-ups, for inclusion in that book. Guiley liked his writing, and the two kept in touch. Eventually, she asked him how The Alchemical Tarot was coming along. At the time, Place was still working full-time as a jeweler, making and selling his own wares. The Alchemical Tarot was therefore progressing very slowly. Guiley decided to help by teaming up with Place, showing him how to create a proposal and, most importantly, get an advance, so he could ease up on jewelry-making and work on the deck and book.

The Alchemical Tarot deck and book set was published in 1995 by Thorsons, a UK subsidiary of HarperCollins. Guiley was listed as a co-author, but in truth Place created almost the whole project. (He believes Guiley deserved the credit, however, because without her help it might never have been published.) The reviews were generally positive, but mixed. “What people found upsetting about the deck at first,” he said, “was that I broke with these cherished traditions, based on my own vision, or on how the alchemists would see it.” He mentions in particular a review by Mary K. Greer, which was in general a “great review,” but in which she took issue with his turning The Chariot around. Other reviewers mentioned the Death card, which they called “icky,” and complained that it might scare people!

The Alchemical Tarot deck and book set was published in 1995 by Thorsons, a UK subsidiary of HarperCollins. Guiley was listed as a co-author, but in truth Place created almost the whole project. (He believes Guiley deserved the credit, however, because without her help it might never have been published.) The reviews were generally positive, but mixed. “What people found upsetting about the deck at first,” he said, “was that I broke with these cherished traditions, based on my own vision, or on how the alchemists would see it.” He mentions in particular a review by Mary K. Greer, which was in general a “great review,” but in which she took issue with his turning The Chariot around. Other reviewers mentioned the Death card, which they called “icky,” and complained that it might scare people!

As time went by, The Alchemical Tarot’s reputation grew. It came out at a time when a lot of Tarot decks were featuring crude artwork, and was an alternative for people who wanted more refined illustrations. Due to a breakdown in relations between the publisher’s UK and US offices, the deck also became rare, and even when it was in print many Americans couldn’t get a copy. This situation has been resolved recently, through Place’s publication of The Alchemical Tarot: Renewed.

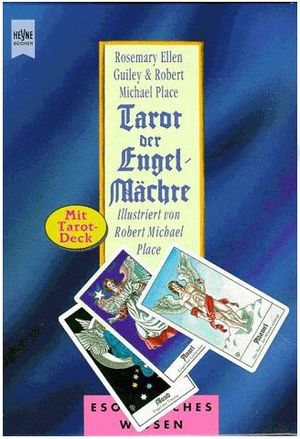

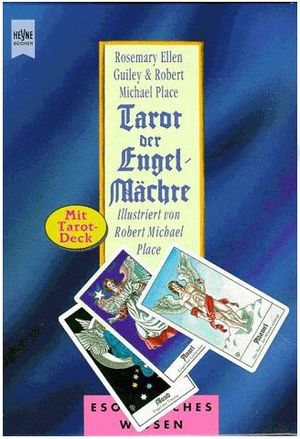

Before the original Alchemical Tarot was even in stores, however, Place was already busy on his next Tarot project: The Angels Tarot. “Rosemary and I were hired by Harper’s San Francisco to do The Angels Tarot, because angels were so popular then,” he explained. In fact, angels were so popular in the mid 1990s that Harper’s feared the bubble might burst any day. They set an ambitious deadline for the Angels deck, and then debated for several months over the contract, with the result that the contract was signed two months before the deck was due. “It was horrendous,” Place remembered. “I had to sit at my drawing table, from the moment I got up in the morning until about one in the morning, every day, seven days a week, for two months, to finish it on time. People would call and want to talk to me, and Rose Ann would say, ‘you’re going to have to wait another month!’”

Because it was done so quickly, Place feels The Angels Tarot to be his least successful deck. For example, because of the time constraints, the deck has plain pip cards, without illustrated scenes; it’s the only deck Place has done where that is the case. On the other hand, Guiley had already done a lot of research on angels, and this helped the two make good choices for angels to represent the trumps. In addition to the fairly obvious choices (Satan for the Devil and Metatron for the Emperor), they also chose some very obscure characters (such as Uzza, a fallen angel suspended between heaven and earth, for The Hanged Man). The immediate response to this was mixed, with some people feeling an angels deck should have had a sentimental, feel-good quality. “I had creepy angels in there,” Place admitted.

Because it was done so quickly, Place feels The Angels Tarot to be his least successful deck. For example, because of the time constraints, the deck has plain pip cards, without illustrated scenes; it’s the only deck Place has done where that is the case. On the other hand, Guiley had already done a lot of research on angels, and this helped the two make good choices for angels to represent the trumps. In addition to the fairly obvious choices (Satan for the Devil and Metatron for the Emperor), they also chose some very obscure characters (such as Uzza, a fallen angel suspended between heaven and earth, for The Hanged Man). The immediate response to this was mixed, with some people feeling an angels deck should have had a sentimental, feel-good quality. “I had creepy angels in there,” Place admitted.

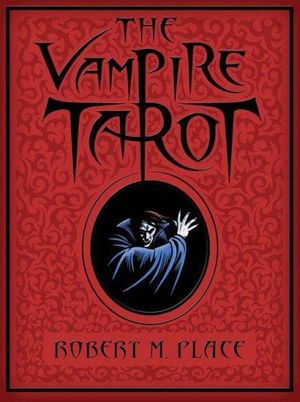

With two decks suddenly on the market, Place had a little down time before the Tarot world came knocking on his door. One thing he did was to establish a business as a professional Tarot Reader, which continues to this day. But for the most part, his proposals for new decks fell on deaf ears. He proposed a vampires Tarot, a saints Tarot, and other ideas, but was told there was a glut of decks on the market, and publishers weren’t buying.

About that time, Place had another moment of inspiration. One night, he went to bed reading about the life of the Buddha. “I woke up,” he said, “and I just realized, ‘Buddha’s story, it’s the Tarot trumps! It’s the same story!” He tried to interest Harper’s in the idea of a Tarot book and deck about the Buddha, to no avail. He listed it as one of the lectures he offered for Tarot fans and other audiences, but no one was interested. He even offered a course on Buddha and the Tarot at Naropa University, a Buddhist school; it was canceled when not enough students signed up. A Buddha Tarot, it seemed, was a non-starter.

About that time, Place had another moment of inspiration. One night, he went to bed reading about the life of the Buddha. “I woke up,” he said, “and I just realized, ‘Buddha’s story, it’s the Tarot trumps! It’s the same story!” He tried to interest Harper’s in the idea of a Tarot book and deck about the Buddha, to no avail. He listed it as one of the lectures he offered for Tarot fans and other audiences, but no one was interested. He even offered a course on Buddha and the Tarot at Naropa University, a Buddhist school; it was canceled when not enough students signed up. A Buddha Tarot, it seemed, was a non-starter.

This all changed in 1999, when the second World Tarot Congress in Illinois finally asked Place to lecture on the Buddha. “They had heard everything before,” he remembered, “and they were looking for a fresh approach to Tarot.” His lecture went very well. More importantly, he met the representatives for Llewellyn, one of the world’s largest publishers of Tarot decks. Chatting with them revealed that they were interested in a Tarot deck depicting saints, and he already had a proposal that had been shot down by Harper’s. Llewellyn’s idea was to publish it simultaneously in English and Spanish, allowing them to tap into the vast market of Latin American Catholics. Within this community, “holy cards” bearing images of saints were already popular items; people carry holy cards with them for comfort and encouragement, and use them in religious rituals. A saints deck for divination was a natural idea. Place quickly sent them a proposal, and received a contract that included a generous advance and enough time to work through the deck.

Tarot of the Saints, and its companion book, A Gnostic Book of Saints, was the first deck and book set Place created without Guiley’s help. It was published in 2001. Like The Angels Tarot, it involved mining Christian symbolism for its connections to Tarot. Also like The Angels Tarot, there were already several obvious points of connection between Tarot and the lore of saints. The Pope is one of the Tarot trumps, and the original Pope, St. Peter, was also one of the earliest Christian saints. Constantine, who converted to Christianity and encouraged the Roman Empire to do the same, was an Emperor. Some images of the Tower had been based on icons of St. Barbara. Unlike the angels project, however, there was enough time for Place to illustrate the pip cards more fully. He believes that both the number and the suit are crucial to the history of divination, and that it is important to represent the suit sign repeated the correct number of times. At the same time, he appreciates the intuitive appeal of pictures on every card. Therefore, he chose to include both a traditional geometric arrangement of pips, and a small scene depicting characters in action. The result is a richly illustrated deck with special resonance for Catholics.

Tarot of the Saints, and its companion book, A Gnostic Book of Saints, was the first deck and book set Place created without Guiley’s help. It was published in 2001. Like The Angels Tarot, it involved mining Christian symbolism for its connections to Tarot. Also like The Angels Tarot, there were already several obvious points of connection between Tarot and the lore of saints. The Pope is one of the Tarot trumps, and the original Pope, St. Peter, was also one of the earliest Christian saints. Constantine, who converted to Christianity and encouraged the Roman Empire to do the same, was an Emperor. Some images of the Tower had been based on icons of St. Barbara. Unlike the angels project, however, there was enough time for Place to illustrate the pip cards more fully. He believes that both the number and the suit are crucial to the history of divination, and that it is important to represent the suit sign repeated the correct number of times. At the same time, he appreciates the intuitive appeal of pictures on every card. Therefore, he chose to include both a traditional geometric arrangement of pips, and a small scene depicting characters in action. The result is a richly illustrated deck with special resonance for Catholics.

Tarot of the Saints has become a very popular deck, among both Anglo-Americans and Latin Americans. Part of the reason is that it recasts the Tarot, which is seen by some Christians as an occult tool and therefore dangerous if not downright evil, into a safe, Christian context. “A lot of people write me letters that say ‘this is the kind of deck I can take out in front of my grandmother, and Grandma won’t think it’s the Devil’s Cards!’” said Place.

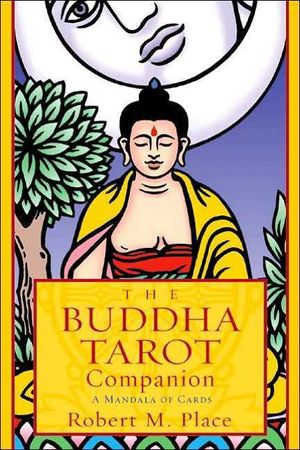

Tarot of the Saints, while it’s a deck to be proud of, was missing one thing as far as Place was concerned. “There wasn’t a coherent story to it,” he lamented. The Alchemical Tarot had been based not only on correspondences between individual images within the two esoteric systems, but also in an overarching story shown in the sequence of trumps, an overarching structure of the deck’s division into suits, and a real historical connection between the two traditions. The intricacy of those connections was very satisfying for Place. Tarot of the Saints had no such intricate story to tell, but his Buddha idea did. So while he was working on Tarot of the Saints, Place made sure to negotiate a contract with Llewellyn for The Buddha Tarot.

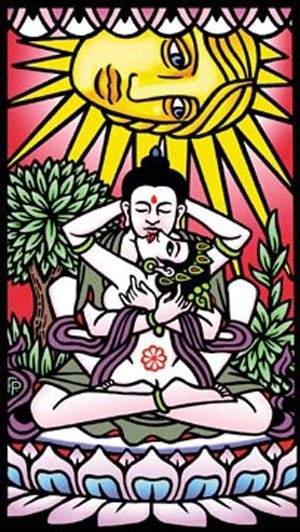

“The Buddha Tarot was the most satisfying thing I had done since The Alchemical Tarot,” Place stated. “As I looked into it, I saw that the story of Siddhartha becoming Buddha was really the same story that’s in the trumps. It has the same three parts, how first he’s a worldly prince then he’s an ascetic and he sees suffering and death, and then he finds the middle path, and achieves enlightenment.” Place also found a strong connection between the Minor Arcana and Buddhism. “In Buddhist tradition,” he explained, “when Siddhartha becomes Buddha, he becomes one with the world. And he becomes one with the sacred map of the world, which is the mandala, which shows the sacred center and the four directions. So he becomes five Buddhas, not just one, the five Jinas, or conquerors.” Four of these Jinas are assigned to a direction; each has a magical symbol, which became the suit symbols in Place’s deck. Each has companions that recall the Tarot court cards: a Sakti, or Queen; a protector animal, which became the Knight; and a Dakini or servant, which became the Knave.

“The Buddha Tarot was the most satisfying thing I had done since The Alchemical Tarot,” Place stated. “As I looked into it, I saw that the story of Siddhartha becoming Buddha was really the same story that’s in the trumps. It has the same three parts, how first he’s a worldly prince then he’s an ascetic and he sees suffering and death, and then he finds the middle path, and achieves enlightenment.” Place also found a strong connection between the Minor Arcana and Buddhism. “In Buddhist tradition,” he explained, “when Siddhartha becomes Buddha, he becomes one with the world. And he becomes one with the sacred map of the world, which is the mandala, which shows the sacred center and the four directions. So he becomes five Buddhas, not just one, the five Jinas, or conquerors.” Four of these Jinas are assigned to a direction; each has a magical symbol, which became the suit symbols in Place’s deck. Each has companions that recall the Tarot court cards: a Sakti, or Queen; a protector animal, which became the Knight; and a Dakini or servant, which became the Knave.

As with his other decks, Place set out his argument in clear, readable prose in the accompanying book, The Buddha Tarot Companion: a Mandala of Cards. Those who read it were often, in his words, “blown away.” It is, in fact, a remarkable book on Tarot, covering in its 366 pages the beginnings of the Tarot, the connections of Tarot with Platonic mysticism, the life of the Buddha, an explication of the mandala, and most importantly, a deep discussion of the connections between these two great traditions. “It’s not that the Tarot was intended to be Buddhist,” Place clarified. “It was made in Renaissance Italy. This is an archetypal structure that we find in both cultures.”

The Buddha Tarot has not been as popular as Tarot of the Saints; although it was released in 2004, two years after Saints, it is being allowed to go out of print while Tarot of the Saints is being reprinted. Still, neither of these is Place’s most sought-after deck. That honor still belongs to The Alchemical Tarot. As noted above, distribution problems plagued this deck, and made it difficult for most people to find a copy. By ten years after its first publication, The Alchemical Tarot was both legendary and unobtainable. One copy famously fetched over two thousand dollars on Ebay, and Place himself sold a copy of the Thorsons edition for almost five hundred dollars. This gave him the idea to provide a better product for a lower price. “I started doing an art edition, giclée prints on archival paper, signed and numbered, with a protective coating. It comes in a wooden box, and sells for three hundred forty dollars.” That edition is still available, but Place has also been able to create a new, mass-market edition of The Alchemical Tarot. With help from fellow Tarot creator Leisa ReFalo, Place worked out a deal. He digitized the images, recomposed them for cards of different dimensions, and self-published them. The result is The Alchemical Tarot: Renewed.

The Buddha Tarot has not been as popular as Tarot of the Saints; although it was released in 2004, two years after Saints, it is being allowed to go out of print while Tarot of the Saints is being reprinted. Still, neither of these is Place’s most sought-after deck. That honor still belongs to The Alchemical Tarot. As noted above, distribution problems plagued this deck, and made it difficult for most people to find a copy. By ten years after its first publication, The Alchemical Tarot was both legendary and unobtainable. One copy famously fetched over two thousand dollars on Ebay, and Place himself sold a copy of the Thorsons edition for almost five hundred dollars. This gave him the idea to provide a better product for a lower price. “I started doing an art edition, giclée prints on archival paper, signed and numbered, with a protective coating. It comes in a wooden box, and sells for three hundred forty dollars.” That edition is still available, but Place has also been able to create a new, mass-market edition of The Alchemical Tarot. With help from fellow Tarot creator Leisa ReFalo, Place worked out a deal. He digitized the images, recomposed them for cards of different dimensions, and self-published them. The result is The Alchemical Tarot: Renewed.

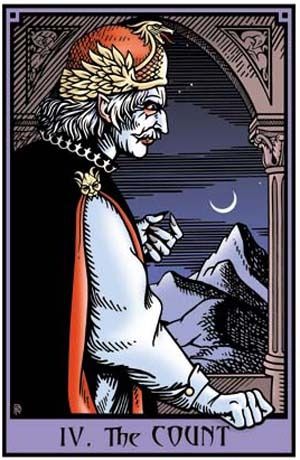

In addition to his decks currently on the market, Place has two decks in development. One of these, The Vampire Tarot, is essentially finished, and will be published at Halloween, 2008, by St. Martin’s Press. After completing The Alchemical Tarot in 1995, Place’s first idea had been to create a vampire deck, based largely on Bram Stoker’s classic novel Dracula. “I saw Dracula as the antithesis of the alchemical quest,” he explained. “The alchemists were looking for the elixir of life, the ‘red elixir,’ that prolongs life indefinitely. And what’s the vampire looking for?”

In addition to his decks currently on the market, Place has two decks in development. One of these, The Vampire Tarot, is essentially finished, and will be published at Halloween, 2008, by St. Martin’s Press. After completing The Alchemical Tarot in 1995, Place’s first idea had been to create a vampire deck, based largely on Bram Stoker’s classic novel Dracula. “I saw Dracula as the antithesis of the alchemical quest,” he explained. “The alchemists were looking for the elixir of life, the ‘red elixir,’ that prolongs life indefinitely. And what’s the vampire looking for?”

In addition, Place points out that “there are symbolic, mythical cross-currents” between Dracula and Arthurian legends in which Guinevere is stolen and must be retrieved—precursors, he said, to the Grail legends. Place pointed out that the novel’s English aristocrat is named Arthur, and that Dracula steals from him the souls of two women, his fiancée Lucy Westenra and her companion Mina Harker. Furthermore, just as in the romances it is Arthur's knights who battle the kidnappers, in Dracula it is Arthur’s friends, Jonathan Harker and Quincey Morris, who battle Dracula, with esoteric lore provided by a Merlin figure, Van Helsing. Harker's experiences in Dracula's castle, for many the most vivid and memorable parts of the novel, are like any number of Arthurian stories in which one of Arthur's knights finds himself in a dangerous castle. Because traditions involving King Arthur and the Grail have been central to occult interpretations of the Tarot, there was a natural area for exploration.

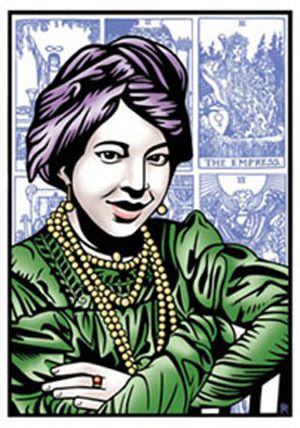

The mid-90s seemed right for such a deck and book; in 1996 Bram Stoker: a Biography of the Author of Dracula, by Barbara Belford, pointed out that Stoker was a close friend of Pamela Colman Smith, the illustrator of the pack known as the Rider Tarot (or the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot), and suggested that Smith’s Tarot designs were an influence on Dracula. Belford had the timing wrong; Stoker completed Dracula years before Smith’s work on the Tarot commenced. However, during the period in which he was writing Dracula, Stoker was friendly with many members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a magical society which used the Tarot, and to which the designer of the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, Arthur Waite, belonged. Indeed, according to some scholars of the Order, Stoker was a member himself, although conclusive proof has been elusive. In any case, through Stoker’s social contact with members of the Order, a direct influence of Tarot themes upon Dracula is quite possible. (Years later, Pamela Colman Smith would join The Golden Dawn as well, leading Place to suggest that Stoker might have influenced Smith to develop an interest in the Tarot, rather than the other way around. If this is the case, we have Dracula to thank for the existence of the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot deck!)

The mid-90s seemed right for such a deck and book; in 1996 Bram Stoker: a Biography of the Author of Dracula, by Barbara Belford, pointed out that Stoker was a close friend of Pamela Colman Smith, the illustrator of the pack known as the Rider Tarot (or the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot), and suggested that Smith’s Tarot designs were an influence on Dracula. Belford had the timing wrong; Stoker completed Dracula years before Smith’s work on the Tarot commenced. However, during the period in which he was writing Dracula, Stoker was friendly with many members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a magical society which used the Tarot, and to which the designer of the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, Arthur Waite, belonged. Indeed, according to some scholars of the Order, Stoker was a member himself, although conclusive proof has been elusive. In any case, through Stoker’s social contact with members of the Order, a direct influence of Tarot themes upon Dracula is quite possible. (Years later, Pamela Colman Smith would join The Golden Dawn as well, leading Place to suggest that Stoker might have influenced Smith to develop an interest in the Tarot, rather than the other way around. If this is the case, we have Dracula to thank for the existence of the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot deck!)

Place points out one point of connection between Dracula and Tarot: the given name of one of the novel’s central characters, Mina, was chosen by Stoker for its resemblance to anima, Latin for soul. This word, among other things, is part of the phrase anima mundi, soul of the world, which in its alchemical form became the dancing female figure on the Tarot’s traditional World card. Others point out that Stoker knew a real-life Mina with connections to the Tarot; Moina Mathers, one of the principal movers in the occult society known as The Golden Dawn, and an important figure in the reinterpretation of the esoteric Tarot in the twentieth century, was born Mina Bergson. Both these aspects of Mina’s name suggest a web of connections among Stoker’s ideas, Stoker’s social circle, and the Tarot deck.

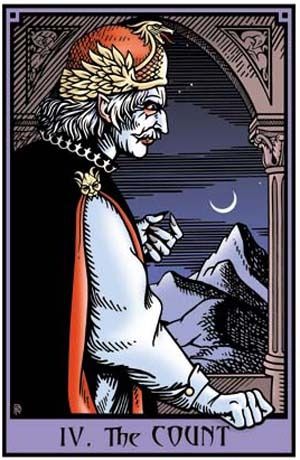

Belford, too, saw a connection, even assigning characters in Dracula to several of the Tarot trumps. Except for the Fool, whose inexperience makes him a good match for Jonathan Harker at the outset of the novel, Place did not find Belford’s correspondences useful, however. “You might think that Dracula is the Devil,” he said by way of example. “But it’s very clear in the novel that he’s not the Devil. He studied with the Devil, so he’s sort of the Devil’s minion.” Place makes Dracula’s card name the Count, to correspond with the Emperor of the traditional Tarot deck. Van Helsing, as a proactive and moralistic leader who insists that the vampire is evil and must be destroyed, seemed a good match for the Hierophant. Mina, whose spiritual strength is more inner-directed, and whose psychic connection with the count helps the others find him, seemed a good High Priestess.

Belford, too, saw a connection, even assigning characters in Dracula to several of the Tarot trumps. Except for the Fool, whose inexperience makes him a good match for Jonathan Harker at the outset of the novel, Place did not find Belford’s correspondences useful, however. “You might think that Dracula is the Devil,” he said by way of example. “But it’s very clear in the novel that he’s not the Devil. He studied with the Devil, so he’s sort of the Devil’s minion.” Place makes Dracula’s card name the Count, to correspond with the Emperor of the traditional Tarot deck. Van Helsing, as a proactive and moralistic leader who insists that the vampire is evil and must be destroyed, seemed a good match for the Hierophant. Mina, whose spiritual strength is more inner-directed, and whose psychic connection with the count helps the others find him, seemed a good High Priestess.

In selecting characters to represent Tarot trumps, Place did not limit himself to the novel Dracula, but also drew on film adaptations, particularly the 1974 TV adaptation produced by Dan Curtis and starring Jack Palance, and the 1992 cinematic version produced by Francis Ford Coppola and starring Gary Oldman. Both these versions include an idea that is absent from Stoker’s novel: one of the female leads (Lucy in Curtis’s version, Mina in Coppola’s) is a reincarnation of Dracula’s fifteenth-century lover. Curtis brought this idea into Dracula from the series Dark Shadows, which he also produced. Place believes it completes the story, among other things (as Curtis himself has pointed out) giving Count Dracula a stronger motivation for moving to England. More importantly, “it evolves the vampire into an animus figure. He’s not just a monster, he also has a lover aspect. And he has something heroic, in a way.” This addition to the story of Dracula helped Place to create a series of trumps that tells a story paralleling that of the traditional Tarot.

The court cards of the Vampire Tarot are historical figures and literary characters. The kings are Stoker and three important men who influenced Dracula; the Queens are similarly important women, including Pamela Colman Smith. The Knights are previous vampire authors who influenced Stoker, and the Knaves are the vampiric characters they created, precursors to Stoker's villain. The pip cards are based on four traditional weapons against vampires. Holy Water replaces Cups, Stakes replace Wands, Garlic Flowers replace Pentacles, and Knives replace Swords. (Some readers may be surprised to find knives in this list; we refer them to Stoker’s novel, in which Dracula himself is killed, not with a stake, but with a kukri and a bowie knife.) As in Tarot of the Saints, on each pip card an arrangement of suit signs is combined with an illustration of a scene; the scenes come from a wide variety of vampire stories.

The court cards of the Vampire Tarot are historical figures and literary characters. The kings are Stoker and three important men who influenced Dracula; the Queens are similarly important women, including Pamela Colman Smith. The Knights are previous vampire authors who influenced Stoker, and the Knaves are the vampiric characters they created, precursors to Stoker's villain. The pip cards are based on four traditional weapons against vampires. Holy Water replaces Cups, Stakes replace Wands, Garlic Flowers replace Pentacles, and Knives replace Swords. (Some readers may be surprised to find knives in this list; we refer them to Stoker’s novel, in which Dracula himself is killed, not with a stake, but with a kukri and a bowie knife.) As in Tarot of the Saints, on each pip card an arrangement of suit signs is combined with an illustration of a scene; the scenes come from a wide variety of vampire stories.

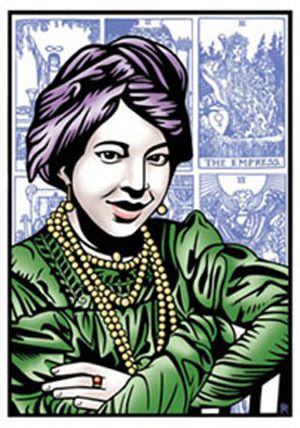

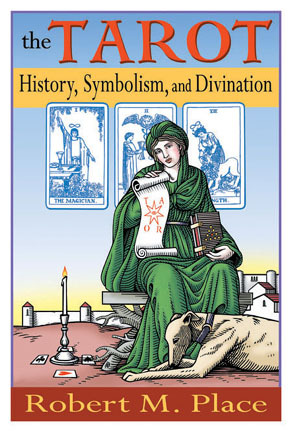

From The Alchemical Tarot to The Vampire Tarot, Place has accompanied each one of his published decks by a substantial book. This has allowed him to communicate a good deal of his thinking and research about Tarot. However, he found that a lot of people didn’t read those books. Moreover, he believed that some of his ideas could benefit from a more general context. For that reason, Place had wanted for some time to write a book that was not a companion to any particular deck. His opportunity came when the editor in chief of Tarcher Books, a division of Penguin, came to one of his lectures at the New York Open Center, and afterward suggested he put his ideas into a book. The resulting tome, The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination, was published in 2005. It combines accurate and up-to-date historical information with Place’s innovative theories.

Since the Tarot was created in Renaissance Italy, Place explained, the challenge in finding out the cards’ original meanings is “to go back there and see how people would have seen them.” Like other historians before him, Place traces the popularity of individual Tarot images before the deck itself was created, focusing extensively on the literature and iconography of triumphs. Poems, drawings, and dramatic enactments of triumphal parades, he argues, became an allegory for the soul’s journey past death and into eternity. “It’s basically a mystical message,” he said.

Since the Tarot was created in Renaissance Italy, Place explained, the challenge in finding out the cards’ original meanings is “to go back there and see how people would have seen them.” Like other historians before him, Place traces the popularity of individual Tarot images before the deck itself was created, focusing extensively on the literature and iconography of triumphs. Poems, drawings, and dramatic enactments of triumphal parades, he argues, became an allegory for the soul’s journey past death and into eternity. “It’s basically a mystical message,” he said.

After showing that, Place takes on the various occultists who have written about the Tarot’s history. “I tried to be fair to the occultists,” he said, “treating their ideas, but also showing all their fallacies. For example, Court de Gébelin, who was the source of every fallacy there is, was also very intuitive, and his intuition was sometimes right on. So he said the Tarot was from ancient Egypt. Well, it wasn’t, but many of the ideas were from Neoplatonism, which WAS from ancient Egypt! And Comte de Mellet split the trumps into three sections representing the three ages of man; that made sense!” Eliphas Lévi’s correspondences between the Tarot trumps and Hebrew letters are shown to be creative, but in Place’s words “unsupported by historical facts.” Place provides a full discussion of the work of Arthur Waite and Pamela Colman Smith, and discusses at length the meanings embodied by the deck they created, The Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot.

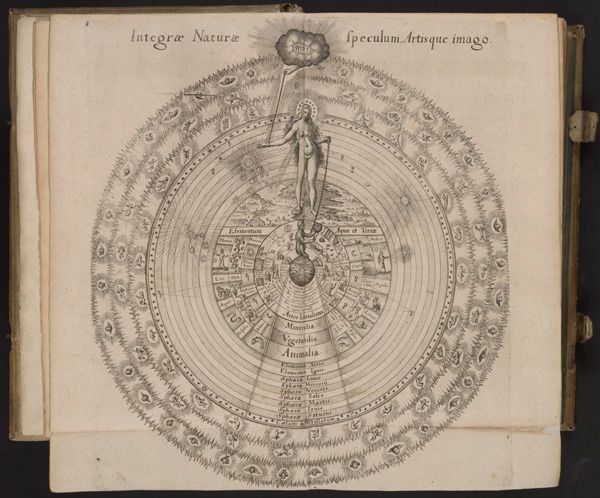

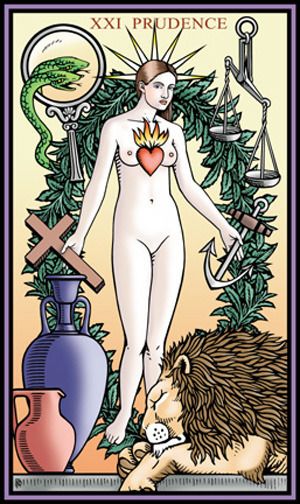

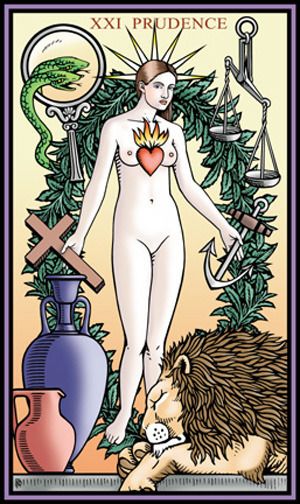

One of Place’s main ideas is that the sequence of trumps is naturally divided into three sets of seven cards. Each one depicts a stage of the soul’s journey to enlightenment in Neoplatonic philosophy. One of his most innovative ideas is part of this argument: that the World is a representation not only of the anima mundi or soul of the world, but also of Prudence. Because it is the only one of the four cardinal virtues not represented by a Tarot card (the other three being Strength, Justice and Temperance), Prudence is often seen as the “missing virtue.” Yet it was very important in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and it seems unlikely to have been omitted. According to Place, the Medieval and Renaissance Neoplatonists saw Prudence as the most important of the four virtues, the sum total of the other three (although Plato himself had ascribed Justice this role). Thus, the attainment of divine enlightenment, symbolized by the World card, was also, for Neoplatonists, the attainment of Prudence, or divine wisdom. Finding the missing virtue, hidden in plain sight, “was my most original contribution,” Place said.

One of Place’s main ideas is that the sequence of trumps is naturally divided into three sets of seven cards. Each one depicts a stage of the soul’s journey to enlightenment in Neoplatonic philosophy. One of his most innovative ideas is part of this argument: that the World is a representation not only of the anima mundi or soul of the world, but also of Prudence. Because it is the only one of the four cardinal virtues not represented by a Tarot card (the other three being Strength, Justice and Temperance), Prudence is often seen as the “missing virtue.” Yet it was very important in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and it seems unlikely to have been omitted. According to Place, the Medieval and Renaissance Neoplatonists saw Prudence as the most important of the four virtues, the sum total of the other three (although Plato himself had ascribed Justice this role). Thus, the attainment of divine enlightenment, symbolized by the World card, was also, for Neoplatonists, the attainment of Prudence, or divine wisdom. Finding the missing virtue, hidden in plain sight, “was my most original contribution,” Place said.

The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination is one of the most influential Tarot books of the last few years. One early review, which appeared in Booklist, stated: “This may be the best book ever written on that deck of cards decorated with mysterious images called the Tarot.” “I think I hit it just right,” Place said. “It went into its third printing in two months!” Even so, Place is not fully satisfied with it; his recent research has turned up new evidence in several areas, and he thinks it may be time to write another Tarot book.

In the meantime, there are other ways to experience Place’s wisdom. He is writing three books in the Mysteries, Legends and Unexplained Phenomena series, for high-school kids: Divination, Shamanism, and Magic & Alchemy. He gives frequent lectures around the New York area, attends Tarot events nationwide, and even leads a Tarot-themed tour of Italy. If you’re not able to travel to him, he also offers classes via conference call, for which he distributes thorough written notes in advance. At his website, http://thealchemicalegg.com/ you can sign up for any of these. You can also purchase examples of his artwork, including prints from his Tarot decks.

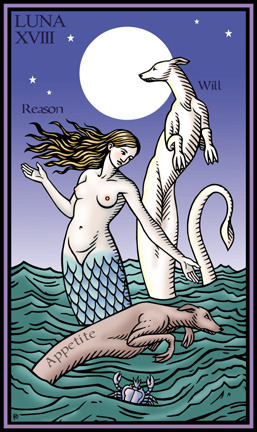

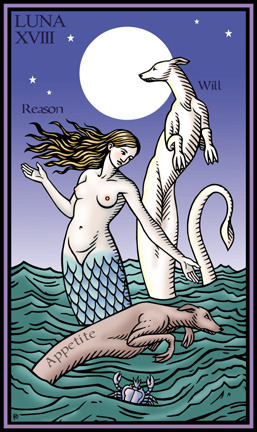

Another thing you’ll find on the web is a selection of cards from his deck-in-progress, entitled Tarot of the Sevenfold Mystery. This deck is based on the western mysticism he discusses in History, Symbolism and Divination. Beginning with Pythagoras and Plato, Place explained, many ancient westerners believed that Earth was in the center of seven crystal spheres, each of which housed a planet. People, they believed, were reincarnated souls, who traveled down these seven layers, or soul centers, to reach earth and be born into flesh. This idea is historically related to the creation (or at least codification) of many systems involving the number seven in western culture; the Christian ideas of seven deadly sins and seven heavenly virtues, the seven notes of the diatonic musical scale, and even the seven chakras common in Indian-derived models of the mind and body, Place argues, were all adopted and codified in the west partly based on these ancient beliefs.

Another thing you’ll find on the web is a selection of cards from his deck-in-progress, entitled Tarot of the Sevenfold Mystery. This deck is based on the western mysticism he discusses in History, Symbolism and Divination. Beginning with Pythagoras and Plato, Place explained, many ancient westerners believed that Earth was in the center of seven crystal spheres, each of which housed a planet. People, they believed, were reincarnated souls, who traveled down these seven layers, or soul centers, to reach earth and be born into flesh. This idea is historically related to the creation (or at least codification) of many systems involving the number seven in western culture; the Christian ideas of seven deadly sins and seven heavenly virtues, the seven notes of the diatonic musical scale, and even the seven chakras common in Indian-derived models of the mind and body, Place argues, were all adopted and codified in the west partly based on these ancient beliefs.

These ideas are also related to ancient and modern mystical practices. Mystics, wishing to regain the beauty and knowledge of Heaven, attempt to reverse the soul’s descent using various methods—meditation, trances, astral projection—and climb the seven levels back through the soul centers, to oneness with the Universe. In this model, chakras are internalizations of the soul centers. Sins or vices are ways in which these soul centers might be out of balance. Virtues are ways to bring them back into balance. By applying the virtues appropriately, a person can travel up the ladder of spheres to enlightenment. Many forms of religious and meditative practice, both in the mainstream and in the New Age movement, follow a similar model.

On a more earthly plane, Place’s deck was inspired by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Coley Burne-Jones. Burne-Jones, he explained, was a latter-day disciple of Italian Renaissance artists Botticelli and Michelangelo. “Botticelli and Michelangelo,” he said, “were the artists who infused this mystical philosophy into western art. Michelangelo studied with Ficino, the great Renaissance Neoplatonist, as a boy.” Influenced by Ficino’s reading of Classical philosophy, Place explained, Botticelli and Michelangelo began the Renaissance tradition of illustrating female nudes as a symbol of higher, spiritual meaning; Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is a prime example of this. “From the 1400s to the 1500s, you can see how Tarot transformed, and incorporated these Neoplatonic Renaissance themes,” he said, “adding the nude on the World and on the Star, as a symbol of spiritual truth.”

On a more earthly plane, Place’s deck was inspired by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Coley Burne-Jones. Burne-Jones, he explained, was a latter-day disciple of Italian Renaissance artists Botticelli and Michelangelo. “Botticelli and Michelangelo,” he said, “were the artists who infused this mystical philosophy into western art. Michelangelo studied with Ficino, the great Renaissance Neoplatonist, as a boy.” Influenced by Ficino’s reading of Classical philosophy, Place explained, Botticelli and Michelangelo began the Renaissance tradition of illustrating female nudes as a symbol of higher, spiritual meaning; Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is a prime example of this. “From the 1400s to the 1500s, you can see how Tarot transformed, and incorporated these Neoplatonic Renaissance themes,” he said, “adding the nude on the World and on the Star, as a symbol of spiritual truth.”

“Getting back to Burne-Jones,” Place continued, “he was influenced by these very same Neoplatonist painters who influenced the Tarot. So his work contained all these themes that you see in Tarot. He painted the Wheel of Fortune, he painted Temperance...it was almost like he was painting Tarot cards and didn’t know it!” At first, Place thought he would create a Burne-Jones Tarot, completing the set of Tarot cards that Burne-Jones hadn’t known he’d been painting. But as he got deeper into the project, he kept coming back what he calls “the sevenfold mystery”: the soul’s journey through seven layers to achieve enlightenment. At the moment, Place has eighteen cards finished, all Major Arcana. Asked what he plans to do for the Minors, he laughed. “That’s a good question,” he said. “I’ll have to think about that!”

Whatever he decides, there’s one thing we can be sure of: the deck will be a true work of art.

By Stephen D. Winick

(Originally Appeared in Tarot World Magazine, 2009)

Robert M. Place is a rarity in the world of Tarot. He is one of the most articulate commentators on the deck’s history, and one of the most meticulous researchers into its meaning. But he is, first and foremost, a visual artist. His unique ability to understand the cards, to explicate them, and to read them, is undoubtedly an extension of his artistic talent and training. In this regard, he joins a select handful of artists who have contributed mightily, not only to the creation of new decks, but to the understanding of old ones. “It’s artists who created the Tarot,” Place reminded me in a May, 2008 interview. “It’s first and foremost a work of art.”

Place has known he was an artist since early childhood. “When I first picked up a crayon,” he said, “I knew, this is it!” Always precocious, he was drawing true-to-life representations of what he saw by the age of seven. He also practiced constantly, bringing his sketch pad everywhere. He recalled a field trip to a colonial house associated with George Washington. Outside, a painter had set up his easel. “While all the other kids were checking out the house, and the woods, I was standing there watching the painter!”

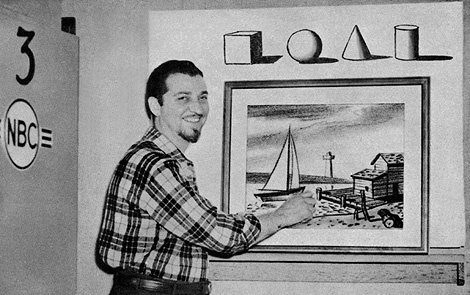

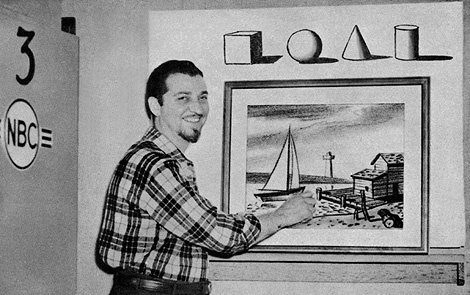

The young Place found influences wherever he saw art, including on TV. He particularly remembers Jon Gnagy, the charismatic Kansas art teacher who was the first act on the first scheduled television broadcast in 1946. Gnagy’s show lasted until 1970, and his method of breaking down forms into basic shapes (“ball, cone, cube, cylinder,” he said at the outset of every show) was an inspiration to millions of aspiring artists, including Place. A film about the muralist Thomas Hart Benton, which Place saw in high school, also remains clear in his mind. “He was working on a mural,” Place remembered. “He drew out the design, and then he made clay sculptures of all the figures, and painted from the clay sculptures, to make sure his shading was all right.” For Place, the message was that art was “a very serious thing, and it takes lots of preparation to do it right.”

Although the first art movement he can remember studying was surrealism, Place was soon more taken with several schools that had predated the surrealists: the Pre-Raphaelites, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones; Symbolism, including John William Waterhouse; and Art Nouveau, which included Aubrey Beardsley. When he was in high school, these movements were out of vogue, Place remembered. But in the late 60s, when he was in college, they were rediscovered. “I remember there was a big retrospective of Aubrey Beardsley at the Huntington Hartford museum in New York. And there started to be all these books on the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolists. And I was avidly collecting all these books, and going to museums to see all these artworks, and learning about Burne-Jones and Rossetti, which anyone can see is a big influence on my work.” In addition, he began to study Renaissance art, and to try his hand at copying it—another clear influence on his later work.

Although the first art movement he can remember studying was surrealism, Place was soon more taken with several schools that had predated the surrealists: the Pre-Raphaelites, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones; Symbolism, including John William Waterhouse; and Art Nouveau, which included Aubrey Beardsley. When he was in high school, these movements were out of vogue, Place remembered. But in the late 60s, when he was in college, they were rediscovered. “I remember there was a big retrospective of Aubrey Beardsley at the Huntington Hartford museum in New York. And there started to be all these books on the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolists. And I was avidly collecting all these books, and going to museums to see all these artworks, and learning about Burne-Jones and Rossetti, which anyone can see is a big influence on my work.” In addition, he began to study Renaissance art, and to try his hand at copying it—another clear influence on his later work. Place’s attention to historical styles brought him into contact with two things that would resonate deeply through his Tarot art: saints and mystical experience. Both came to him through his work with Russian painters of icons, stylized paintings of Orthodox saints. This began one summer, when he accompanied a Russian friend to a monastery in upstate New York where the monks were famed artists. “They would put gold leaf down by taking wads of monks’ bread and pounding it on the gold, and pounding it into the gum that they had already painted on the surface,” he remembered. “So they were basically using medieval techniques.” It was those techniques that fascinated Place, and he began to learn them himself, traveling to the monastery several more times for further study.

Place’s attention to historical styles brought him into contact with two things that would resonate deeply through his Tarot art: saints and mystical experience. Both came to him through his work with Russian painters of icons, stylized paintings of Orthodox saints. This began one summer, when he accompanied a Russian friend to a monastery in upstate New York where the monks were famed artists. “They would put gold leaf down by taking wads of monks’ bread and pounding it on the gold, and pounding it into the gum that they had already painted on the surface,” he remembered. “So they were basically using medieval techniques.” It was those techniques that fascinated Place, and he began to learn them himself, traveling to the monastery several more times for further study. While studying with the monks, he became aware that, as he put it, “the paintings themselves were magical.” He experienced this himself, while looking at an icon of Boris and Gleb, the earliest Russian saints. “The panel was split between the two brothers,” he said. “One had his right hand up and his left hand down, and the other had his left hand up and his right hand down. One had a red inner garment and a blue outer garment, and the other a blue inner garment and red outer garment. It created this duality that kept being reconciled by the two. I kept looking back and forth, from one side to the other, and this wave of energy came off the icon, and just blasted into me. The rest of the day, I was in this incredible high state, where everything was incredibly beautiful, and I just wandered around the monastery, awestruck.”

Art, sacredness and mysticism…all seemed to be in position for Place’s rendezvous with the Tarot. Although in college he had been aware of the Tarot through his studies of esoteric art, had sketched four cards of a deck based on the Tarot of Marseilles, and had dated a woman who read Tarot, he hadn’t gotten deeply involved at the time. But later, in 1982, when he and his wife Rose Ann had established a business making jewelry, the Tarot magically entered his life, through a dream.

Place dreamed that he was in a building, and a phone rang. He picked it up, and a dream operator connected him to a secretary with a law firm. She told him he had an inheritance coming from an ancestor in England. She could not tell him what it was, but he would know it when he saw it. She said it came with a karmic debt incurred by his ancestor, who had misused it in some way. She also told him it would come in a box, and it was called “the key.” Place agreed to accept the gift, and the debt that came with it.

“The dream was so vivid that I just expected that when I woke up, the box would be there at the foot of the bed,” he marveled. “That was a bit naïve, but considering what happened later, it wasn’t that naïve. Because within days, my friend Scott came over, with the Waite-Smith deck that he’d just received in the mail. As he walked in the door, my head turned involuntarily, and my eyes focused on the deck, and I instantly recognized that that was the thing from England. It comes in a box, it was first published in England, the original book [that described it] was Key to the Tarot, the trumps were called keys…I said, ‘oh, of course, it’s the Tarot!’ It was so obvious, as soon as I saw it!” Within a few more days, another friend who had an extra Marseilles deck came to visit Place and said, “I thought you needed a Tarot deck.” Soon after that, he bought his own Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, and the inheritance was complete.

“The dream was so vivid that I just expected that when I woke up, the box would be there at the foot of the bed,” he marveled. “That was a bit naïve, but considering what happened later, it wasn’t that naïve. Because within days, my friend Scott came over, with the Waite-Smith deck that he’d just received in the mail. As he walked in the door, my head turned involuntarily, and my eyes focused on the deck, and I instantly recognized that that was the thing from England. It comes in a box, it was first published in England, the original book [that described it] was Key to the Tarot, the trumps were called keys…I said, ‘oh, of course, it’s the Tarot!’ It was so obvious, as soon as I saw it!” Within a few more days, another friend who had an extra Marseilles deck came to visit Place and said, “I thought you needed a Tarot deck.” Soon after that, he bought his own Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, and the inheritance was complete. Early on, Place tried to learn about Tarot by reading books. From his own studies in art history, however, he found many of the historical claims in books unlikely. Instead, he decided to learn from the pictures. With long experience in reading pictures, he discovered much of the esoteric information encoded into the cards by Waite, and by the generations of Tarot creators before him. From broad correspondences, such as that of the four elements with the four suits, to individual plant and animal symbols, Place was able to read the cards with ease. Beginning with the Celtic Cross layout, Place soon found himself dissatisfied with its limitations. He created his own method of reading involving several groups of three cards, which he teaches to this day. For years, he did Tarot readings for free, for anyone who asked, as a way of discharging the karmic debt that had come with his cards.

Getting more deeply involved with Tarot, and being aware that the deck itself was a creation of Renaissance Italy, Place also began to return to his studies of Renaissance art, with the Tarot as a focus. He examined esoteric principles, such as those of alchemy, and related ideas of Gnosticism and Neoplatonism. Naturally, the connections among all these Renaissance systems hit him most strongly when he was looking at a work of art, in this case an alchemical illustration of the Philosopher’s Stone. “There was a heart in the center of a cross that divided the background into four sections,” he said, “and there was an image of one of the four elements in each section, one to each corner. And there were five drops of blood coming off the heart, and a crown of thorns around it, and a rosebud coming up out of the top.”

Place realized that he was looking at the symbolic equivalent of the World card from the Tarot deck…and was, quite literally, inspired by the revelation. “The heart is a symbol of the soul,” he reasoned. “And the woman on the World card is a symbol of the soul. And the four evangelists [on the World card] are associated with the four elements in medieval symbolism. And the wreath [on the World card] is like the crown of thorns. So this was really interchangeable. And when I realized that, again, a wave of energy came off the picture, just like what happened with the icon. And in a flash, I saw that the whole deck was alchemical… images were flooding out, and I began to see how every card in the whole Tarot deck was interchangeable with alchemical things I had seen.”

It wasn’t just a matter of individual images in the Tarot corresponding with individual alchemical concepts; it was also the whole design of the deck that seemed systematically alchemical. If the ultimate goal of alchemy was the Philosopher’s Stone, and the ultimate goal of the trumps sequence was the World, and the two turned out to be interchangeable, it seemed likely that “the story in the trumps was the same story, the story of the Great Work or the Opus [in alchemy], of finding the Philosopher’s Stone.” In addition, Place realized that there is an alchemical structure inherent to the Tarot deck, with four minor suits corresponding to the four elements, a fifth suit of trumps corresponding to the quinta essentia, or fifth element, and the World card reconciling all these images into the final achievement of the Great Work.

“It’s like it opened some secret door in my brain,” Place said. He stepped through that door, and found himself designing his first deck, The Alchemical Tarot. He began by further researching alchemical images, including C. G. Jung’s use of alchemical symbolism in Psychology and Alchemy. Then he began the illustrations, using several methods to devise his card concepts. “I was trying to understand the cards as they originally were understood in the Renaissance,” he explained. “I looked though many different alchemical images to see how they fit, and sometimes I took aspects of several different alchemical images, and put them together with certain Tarot aspects.” Thus, his World card borrows aspects of the alchemical design for the Philosopher’s Stone, but also includes the Ouroboros, a common alchemical motif, and a nude female figure representing the anima mundi, an important figure in Platonic and alchemical thought, who also appears on more traditional World cards.

Another approach led to some of the more unusual images in the deck. He adopted the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn’s method of doing guided meditations (or as he now calls them, shamanic journeys) in which he visualized the cards as doors, passed through the doors, and interacted with the characters he found. He included aspects of many of these visions in his card designs. For example, behind the door of the Chariot card, he found a chariot much like the one on more traditional cards, driven by a very youthful driver. The driver turned the chariot around, and invited Place to get on the back with him. The two flew off on a journey together, flying high in the air, to witness a wheel of sunrises in the sky, with larger sun at the center. Place recognized this central sun as the internal sun, an important alchemical concept. Place’s Chariot card reflects this vision: the chariot is turned around, facing away from the observer, who is invited to get aboard; above, the vision of the suns is clearly visible.

Another approach led to some of the more unusual images in the deck. He adopted the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn’s method of doing guided meditations (or as he now calls them, shamanic journeys) in which he visualized the cards as doors, passed through the doors, and interacted with the characters he found. He included aspects of many of these visions in his card designs. For example, behind the door of the Chariot card, he found a chariot much like the one on more traditional cards, driven by a very youthful driver. The driver turned the chariot around, and invited Place to get on the back with him. The two flew off on a journey together, flying high in the air, to witness a wheel of sunrises in the sky, with larger sun at the center. Place recognized this central sun as the internal sun, an important alchemical concept. Place’s Chariot card reflects this vision: the chariot is turned around, facing away from the observer, who is invited to get aboard; above, the vision of the suns is clearly visible. A third card that benefited from Place’s intuition was Justice. At first, he used a Renaissance drawing as a model, added a crown and a pair of scales, and decided that the scales would weigh fire against water, based on alchemical principles. He gave Justice a sword, and on the hilt put the alchemical symbol for vitriol, which had seen in an alchemical design. Place then added fire and smoke coming out of Justice’s crown, and an eye of consciousness in the flames, “totally on a whim,” he said. The figure stood between two columns, with the scales in front of one and the sword in front of the other. As Place looked at the image he had drawn, he recognized two things. First, with the crown of smoke and fire, Justice had become a third and central column. Second, the three-column arrangement resembled the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, in which the left column represents severity, the right column represents mercy, and the central column, representing balance or equilibrium, culminates on top with the crown, and leads to God-consciousness, represented by the eye.

This in turn taught Place some lessons about justice. “The column of mercy is the one with the sword, and severity is the one with the scales,” he observed. “Severity meant that you couldn’t allow your emotions to interfere when you were weighing out things, and tying to find out the truth…you’ve got to be impartial. Whereas mercy, that was the sword, because the sword was punishment.” In Place’s view, then, severity in the search for truth is appropriate, if it is tempered by mercy in the application of punishment. “A lot of people might think it should go the other way,” he said, “but I think that’s the problem! In the United States we have five percent of the world’s population, but twenty-five percent of the world’s prisoners, because we’re so vindictive!”

This in turn taught Place some lessons about justice. “The column of mercy is the one with the sword, and severity is the one with the scales,” he observed. “Severity meant that you couldn’t allow your emotions to interfere when you were weighing out things, and tying to find out the truth…you’ve got to be impartial. Whereas mercy, that was the sword, because the sword was punishment.” In Place’s view, then, severity in the search for truth is appropriate, if it is tempered by mercy in the application of punishment. “A lot of people might think it should go the other way,” he said, “but I think that’s the problem! In the United States we have five percent of the world’s population, but twenty-five percent of the world’s prisoners, because we’re so vindictive!”All this journeying, drawing and learning took time. It would be years before Place finished The Alchemical Tarot, during which time, he says, odd synchronicities occurred. He described one in particular, which led to his becoming a writer, and to the publication of The Alchemical Tarot: soon after he began studying Gnosticism, he came across the now-defunct magazine Gnosis in a health food store, while shopping with his wife and his friend Sue. At Sue’s urging, he bought the magazine. He read it, loved it, and subscribed. Soon after that, something told him Gnosis would soon do an issue on the Tarot, and that he should share some of his work. He sent them copies of several of the original drawings, including the Star. A week or so later, he received a phone call from the publisher, Jay Kinney.

While it was not true that Gnosis was planning a Tarot issue, it was true that they had been specifically seeking an illustration of Sophia, goddess of wisdom. Gnosis bought the illustration on Place’s Star card, and also asked Place to write a one-page article on The Star. Both appeared in 1989, in issue 13 of Gnosis, as a sidebar to an article on Sophia by Caitlín Matthews. This was the first piece of writing Place published.

While it was not true that Gnosis was planning a Tarot issue, it was true that they had been specifically seeking an illustration of Sophia, goddess of wisdom. Gnosis bought the illustration on Place’s Star card, and also asked Place to write a one-page article on The Star. Both appeared in 1989, in issue 13 of Gnosis, as a sidebar to an article on Sophia by Caitlín Matthews. This was the first piece of writing Place published.The sidebar and illustration came to the attention of Rosemary Ellen Guiley, who was working on her book The Mystical Tarot. She contacted Place, and asked him for several more illustrations, with brief write-ups, for inclusion in that book. Guiley liked his writing, and the two kept in touch. Eventually, she asked him how The Alchemical Tarot was coming along. At the time, Place was still working full-time as a jeweler, making and selling his own wares. The Alchemical Tarot was therefore progressing very slowly. Guiley decided to help by teaming up with Place, showing him how to create a proposal and, most importantly, get an advance, so he could ease up on jewelry-making and work on the deck and book.

The Alchemical Tarot deck and book set was published in 1995 by Thorsons, a UK subsidiary of HarperCollins. Guiley was listed as a co-author, but in truth Place created almost the whole project. (He believes Guiley deserved the credit, however, because without her help it might never have been published.) The reviews were generally positive, but mixed. “What people found upsetting about the deck at first,” he said, “was that I broke with these cherished traditions, based on my own vision, or on how the alchemists would see it.” He mentions in particular a review by Mary K. Greer, which was in general a “great review,” but in which she took issue with his turning The Chariot around. Other reviewers mentioned the Death card, which they called “icky,” and complained that it might scare people!

The Alchemical Tarot deck and book set was published in 1995 by Thorsons, a UK subsidiary of HarperCollins. Guiley was listed as a co-author, but in truth Place created almost the whole project. (He believes Guiley deserved the credit, however, because without her help it might never have been published.) The reviews were generally positive, but mixed. “What people found upsetting about the deck at first,” he said, “was that I broke with these cherished traditions, based on my own vision, or on how the alchemists would see it.” He mentions in particular a review by Mary K. Greer, which was in general a “great review,” but in which she took issue with his turning The Chariot around. Other reviewers mentioned the Death card, which they called “icky,” and complained that it might scare people!As time went by, The Alchemical Tarot’s reputation grew. It came out at a time when a lot of Tarot decks were featuring crude artwork, and was an alternative for people who wanted more refined illustrations. Due to a breakdown in relations between the publisher’s UK and US offices, the deck also became rare, and even when it was in print many Americans couldn’t get a copy. This situation has been resolved recently, through Place’s publication of The Alchemical Tarot: Renewed.