St. George and the Book Dragon: Introduction

On December 18 and 19, 2012, a costumed band of merrymakers roamed the halls of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., singing traditional carols, performing an unusual version of a centuries-old folk play, and playing tunes on accordion, fiddle, whistle, and recorder. Like the Druids of Spinal Tap’s “Stonehenge,” these itinerant actors and musicians remain a great mystery: “no one knows who they were or what they were doing.”

Well, that’s not quite true. My friends and I know. In fact, as Tama Janowitz might say, “They Is Us.”

Well, that’s not quite true. My friends and I know. In fact, as Tama Janowitz might say, “They Is Us.” So, who were they? Members of the staff of the American Folklife Center, the Library’s folklore archive and study center. What were they doing? Engaging in an age-old tradition known as a Mummers Play. We have been performing a Mummers Play at the Library since 2009, making this our fourth annual mumming.

What is a Mummers Play, you ask, and what is mumming? To answer that, I’ll quote myself, from a post I wrote last year.

Mumming, or disguising oneself, going door to door, and performing in neighbors' homes and in public places, is a very old and widespread custom in Europe, going back at least to the middle ages. However, the type of play we call a Mummers Play today may not go back any further than the eighteenth century, since earlier references to "mumming" either are vague about the exact type of performance, or are clearly a different kind of play.

Modern Mummers Plays typically involve a fight between two champions, one of whom is killed. A doctor then revives the dead hero. In their death-and-resurrection theme, they clearly resonate not only with Christian beliefs, but also with earlier pagan beliefs, leading some to theorize that they are vestiges of pre-Christian ceremony. My own feeling is that they reflect vestiges of pre-Christian thought within Christianity itself, making them pagan in flavor but Christian in origin. Plays of this type are widespread throughout the English-speaking world, including Britain, Ireland, Newfoundland and other parts of Canada, Kentucky, and St. Kitts and Nevis.

To add to last year’s explanation, I’ll mention that mumming in Britain, Ireland, and Canada mostly occurs around the Winter Solstice, which makes the death-and-resurrection theme resonate with the world outside the play. It also places the play at a time of year when the nights are long and boring, and people particularly appreciate entertainment.

Mumming also occurs when the plenty of the earth has abated for the season, and some members of the community are facing lean times. The play, which is often performed in exchange for food, drink, or money, allows people to informally redistribute wealth toward those who need it, spreading holiday cheer throughout the community. Although we perform our play for free, some of the performances occur at holiday parties where the various divisions offer us food and drink, keeping us in touch with these ancient roots of the mumming tradition.

The American Folklife Center, where we mummers work, is lucky to have a collection particularly rich in Mummers Play texts, the James Madison Carpenter Collection. [See also the online catalog.] During his fieldwork in Britain in the 1930s, Carpenter collected over five hundred texts of folk plays. In 2009, it occurred to Folklife Specialist Jennifer Cutting to adapt a new version of the Mummers Play from the Carpenter materials. She enlisted my aid, and the two of us produced the first script in that year. The following year, we changed it; since one of our actors happens to be from St. Kitts and Nevis, where an unusual version of the Mummers Play has been documented, I added her character, the dragon, from a Caribbean version. We also began to add topical references, which is a traditional aspect of Mummers Play performances. Ours centered on aspects of our lives as Library of Congress employees.

The American Folklife Center, where we mummers work, is lucky to have a collection particularly rich in Mummers Play texts, the James Madison Carpenter Collection. [See also the online catalog.] During his fieldwork in Britain in the 1930s, Carpenter collected over five hundred texts of folk plays. In 2009, it occurred to Folklife Specialist Jennifer Cutting to adapt a new version of the Mummers Play from the Carpenter materials. She enlisted my aid, and the two of us produced the first script in that year. The following year, we changed it; since one of our actors happens to be from St. Kitts and Nevis, where an unusual version of the Mummers Play has been documented, I added her character, the dragon, from a Caribbean version. We also began to add topical references, which is a traditional aspect of Mummers Play performances. Ours centered on aspects of our lives as Library of Congress employees.  For the 2012 play, we decided on two new themes to introduce. One had to do with a question of major importance to the Library world: the impact of digital technology, especially e-books, on reading and the library profession. The idea came from Theadocia Austen, who suggested that the battle should be between books and e-books. The second theme was purely for fun: both Thea and fellow actor, collaborator, and Carpenter Collection curator Jennifer Cutting are steampunk enthusiasts, and wanted some references to both the literary genre and the associated dress style added to the play.

For the 2012 play, we decided on two new themes to introduce. One had to do with a question of major importance to the Library world: the impact of digital technology, especially e-books, on reading and the library profession. The idea came from Theadocia Austen, who suggested that the battle should be between books and e-books. The second theme was purely for fun: both Thea and fellow actor, collaborator, and Carpenter Collection curator Jennifer Cutting are steampunk enthusiasts, and wanted some references to both the literary genre and the associated dress style added to the play. With our two new ideas and the many aspects of traditional mumming buzzing around in my head, I set out to craft our new play. One challenge arose almost immediately. We are library professionals, and the Library of Congress is an important voice in setting policy and practice in the library world. We knew we would be performing the play in front of a lot of librarians with their own well-thought-out positions. Also, we knew the play would be witnessed by members of the public who might see it as sanctioned by the Library of Congress. Therefore, we didn’t want to take a position on the relative value of books and e-books, which might be contrary to the Library’s official positions or offend the feelings of individual librarians. The Mummers Play structure, however, necessitates conflict, and usually establishes a clear hero and villain. It was therefore our challenge to reconcile the enemies before the end of the play.

To accomplish this, we used a strategy we had previously employed in The Newfoundland-and-Saskatchewan Squid-and-Bigfoot Mummers Play and Mock Wedding, which celebrated the retirement of Michael Taft in 2011: we imported elements of another traditional folk drama genre, the “mock wedding.” Mock weddings are performances that make fun of traditional weddings by subverting elements of the ceremony, especially the wedding vows, and using them to highlight common or stereotypical conflicts between the sexes. In typical examples, the “woman” (usually played by a man) vows to take charge and make the man miserable, and the “man” (usually played by a woman) vows to give up all fun and submit to his wife. The mock wedding lines we used in St. George and the Book Dragon were collected by Michael Taft in North Dakota. By adding a mock wedding to the end of our play, we reconciled our book and e-book advocates, while still suggesting they had an interesting life ahead of them, marked by unpredictable and potentially awkward power dynamics.

To accomplish this, we used a strategy we had previously employed in The Newfoundland-and-Saskatchewan Squid-and-Bigfoot Mummers Play and Mock Wedding, which celebrated the retirement of Michael Taft in 2011: we imported elements of another traditional folk drama genre, the “mock wedding.” Mock weddings are performances that make fun of traditional weddings by subverting elements of the ceremony, especially the wedding vows, and using them to highlight common or stereotypical conflicts between the sexes. In typical examples, the “woman” (usually played by a man) vows to take charge and make the man miserable, and the “man” (usually played by a woman) vows to give up all fun and submit to his wife. The mock wedding lines we used in St. George and the Book Dragon were collected by Michael Taft in North Dakota. By adding a mock wedding to the end of our play, we reconciled our book and e-book advocates, while still suggesting they had an interesting life ahead of them, marked by unpredictable and potentially awkward power dynamics.  The characters in our play were a combination of traditional and new elements. “St. George of Merry England” is often the hero of mummers plays, but oddly, he is sometimes the son of the “King of Egypt.” Given that e-books was one of our themes, it seemed significant that the names of these two countries both begin with E; I took it as a sign that our hero should be “St. George of Merry E-Land,” and that his father should be the “King of E-Readers.” In these roles, I cast Brock Thompson and Bertram Lyons, who both had played St. George in previous Mummers Plays. Bert, who is AFC’s digital assets manager, was a particularly appropriate “digital dude,” and also came up with the idea of naming his character “Schnook,” after a line I wrote for the play.

The characters in our play were a combination of traditional and new elements. “St. George of Merry England” is often the hero of mummers plays, but oddly, he is sometimes the son of the “King of Egypt.” Given that e-books was one of our themes, it seemed significant that the names of these two countries both begin with E; I took it as a sign that our hero should be “St. George of Merry E-Land,” and that his father should be the “King of E-Readers.” In these roles, I cast Brock Thompson and Bertram Lyons, who both had played St. George in previous Mummers Plays. Bert, who is AFC’s digital assets manager, was a particularly appropriate “digital dude,” and also came up with the idea of naming his character “Schnook,” after a line I wrote for the play.To contrast with St. George and Schnook, I needed characters who loved books. I first thought of our wonderful dragon costume, created by Stephanie Hall for last year’s play, and decided a “Book Dragon” would be a good starting place, especially since Valda Morris was already so good at playing the Dragon. For the character of her father, I remembered that “wyrm” was an old word for Dragon, and “bookworm” slang for a book-lover. “The Old Bookworm” had a mummerish feel to it, and I settled on that. This character was essentially a version of the Beelzebub role we usually include in our play, so I cast the actor who had portrayed Beelzebub marvelously in the previous year, David Quick.

We have typically begun and ended our play with speeches by fools. The opening fool has been known as “Hind-Before,” a name that occurs in the Carpenter Collection, and “Bass-Ackwards,” a more modern version of the same idea. This year, the actor who usually performs this role was ill, so we opted to change the play, incorporating the fools “Poor” and “Mean,” also found in the Carpenter Collection. As we got closer to the production, another of our actors caught the flu and lost her voice, so we combined both into one character, “Poor & Mean,” who was ably portrayed by Pete Sullivan.

We have typically begun and ended our play with speeches by fools. The opening fool has been known as “Hind-Before,” a name that occurs in the Carpenter Collection, and “Bass-Ackwards,” a more modern version of the same idea. This year, the actor who usually performs this role was ill, so we opted to change the play, incorporating the fools “Poor” and “Mean,” also found in the Carpenter Collection. As we got closer to the production, another of our actors caught the flu and lost her voice, so we combined both into one character, “Poor & Mean,” who was ably portrayed by Pete Sullivan. The fool who closes our play is always performed by Jennifer Cutting. We change the character’s name each year, but her performance is always similar; after a brief speech, she commands the mummers to dance, and plays the tune on her accordion. This year, she was known as “Bumruffle,” after a small bustle that is part of some Victorian dress styles. Bumruffle also acted as the leader of the village band, made up of Catherine Kerst (fiddle), Ann Hoog (recorder), and Nancy Groce (pennywhistle).

The characters were rounded out by my own, Father Christmas, a traditional Mummers Play figure, who acts rather like a master of ceremonies for the play.

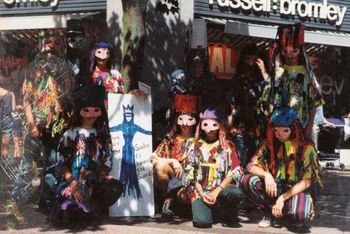

The costuming for our play drew inspiration from various time periods and themes. Our dragon wore the most elaborate costume, created for us last year by Stephanie Hall. Poor & Mean wore a medieval-style doublet and a tall conical hat made of colored tinsel, which is a modern take on a traditional mummer’s hat. Schnook wore a fur-trimmed cloak and Mardi Gras crown, and under it a fantastic e-reader costume created by Bert, following the time-honored mummer’s tradition of creating one’s own disguises.

Father Christmas sported the most traditional look, with a cloak, high boots, a tall staff, and a head-wreath made of holly. St. George was likewise very traditional, with a white tunic bearing the red Cross of St. George.

Father Christmas sported the most traditional look, with a cloak, high boots, a tall staff, and a head-wreath made of holly. St. George was likewise very traditional, with a white tunic bearing the red Cross of St. George. Three characters were dressed in the mixture of Victorian dress and technological accessories widely known as Steampunk. The Old Bookworm was the most Victorian; in fact, his look was inspired by Carl Spitzweg's 1850 painting Der Bücherwurm, a Victorian Romantic masterpiece. We merely added a top hat and walking-stick (which Der Bücherwurm himself would have had, had he been outdoors), and a steampunk eyepatch-monocle, to complete his look. Bumruffle mixed her steampunk elements with bright clown colors, wearing a corset, a bustle, long striped bloomers, striped stockings, fingerless lace gloves, and—of course—a tiny hat. Her black, white, and red color-scheme was based on that of her classic Dino Baffetti diatonic button accordion. Her small, spectacle-style goggles were a vintage pair purchased at the famous New York “antiques & oddities” shop, Obscura, and to complete her clown outfit she carried a rubber chicken under her arm.

Doctor Terpsichore Snark, played by Theadocia Austen (whose own name was apparently not Steampunk enough), wore our most complete Steampunk outfit, including top hat, machinist goggles, corset, skirt, jacket, bustle, boots, and a necklace made of watch parts. She even arrived with her own airship—or at least, a mounted poster of one! Her only concession to mumming tradition was a toy stethoscope.

Doctor Terpsichore Snark, played by Theadocia Austen (whose own name was apparently not Steampunk enough), wore our most complete Steampunk outfit, including top hat, machinist goggles, corset, skirt, jacket, bustle, boots, and a necklace made of watch parts. She even arrived with her own airship—or at least, a mounted poster of one! Her only concession to mumming tradition was a toy stethoscope.The verse of our Mummers Play came from two basic sources: old folk plays and my own imagination. Certain speeches, such as my Father Christmas lines, are mostly traditional, with small Library references added in for seasoning. Others, such as the lines of the Old Bookworm, are completely original to our play. Still others, especially those of the Doctor, are traditional in their structure, but have been altered to give them a steampunk flavor. I should also mention that ad-libs by the actors added some great touches to the play. Wherever possible, they have been incorporated into the final version of the script, making the end product a collaborative effort of all the mummers. Our hope is that the joining of traditional and original material is relatively seamless. However, in some cases it will be obvious that verses directly relating to libraries or to steam-powered technology have been added by me and the players.

I know what you’re thinking: enough about the production! Where’s the Play?

Here it is!